Recognition of Learning TOC

Key Highlights of this Brief

This brief draws on data from a survey administered to 1,184 current undergraduate students and from interviews with six college students.

- Students gain college-level learning outside of the classroom in a variety of ways. Adult learners in this study were more likely to report work experience, completing a certificate or professional license, or enlisting in the military; students under the age of 25 were more likely to report having taken an AP/IB course or volunteer experience.

- Students cited conversations with individuals (such as high school counselors, counselors or academic advisors on the college campus, other students, or family members) as the main sources of knowledge about PLA, not written material on college catalog.

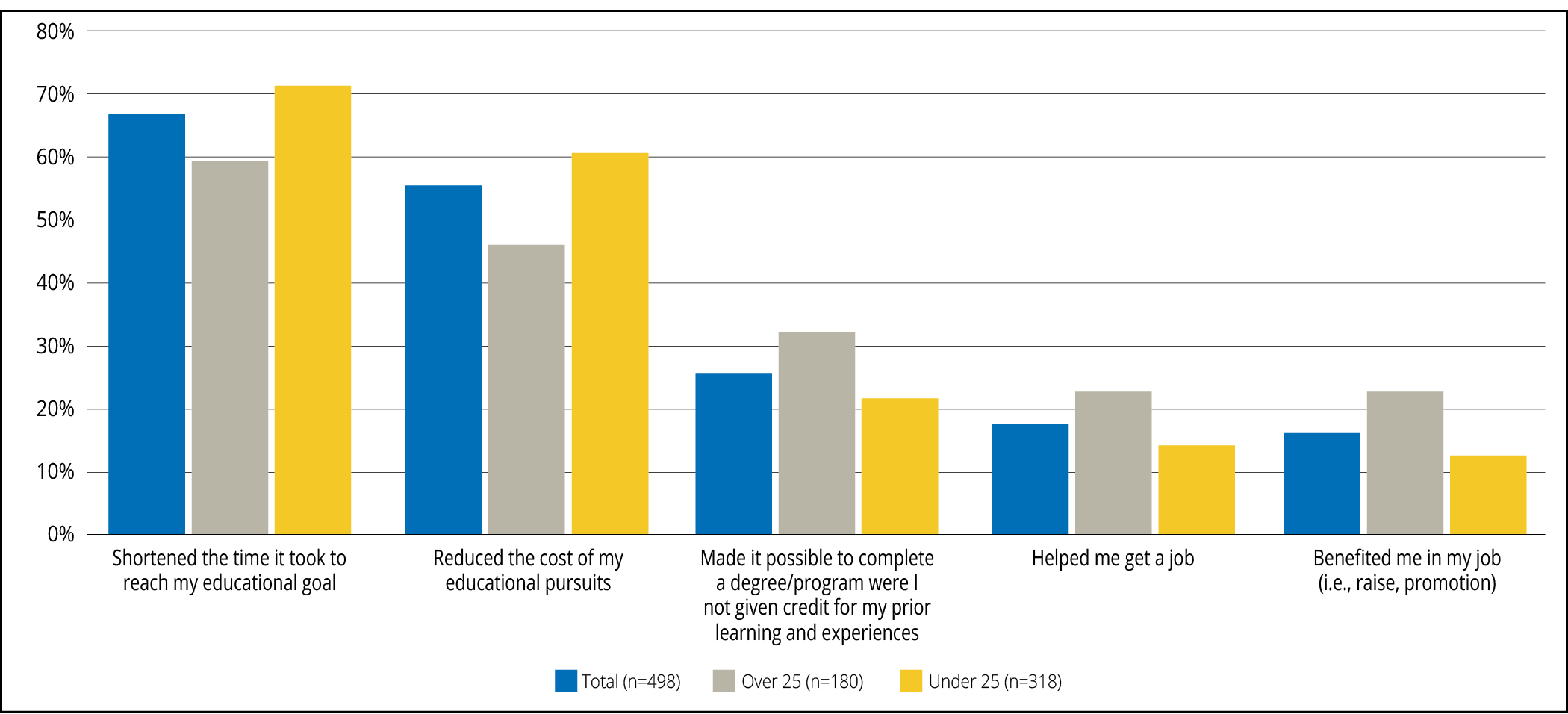

- Students cited time and cost savings as two benefits to their college career from PLA. Adult learners also cited benefits to their careers.

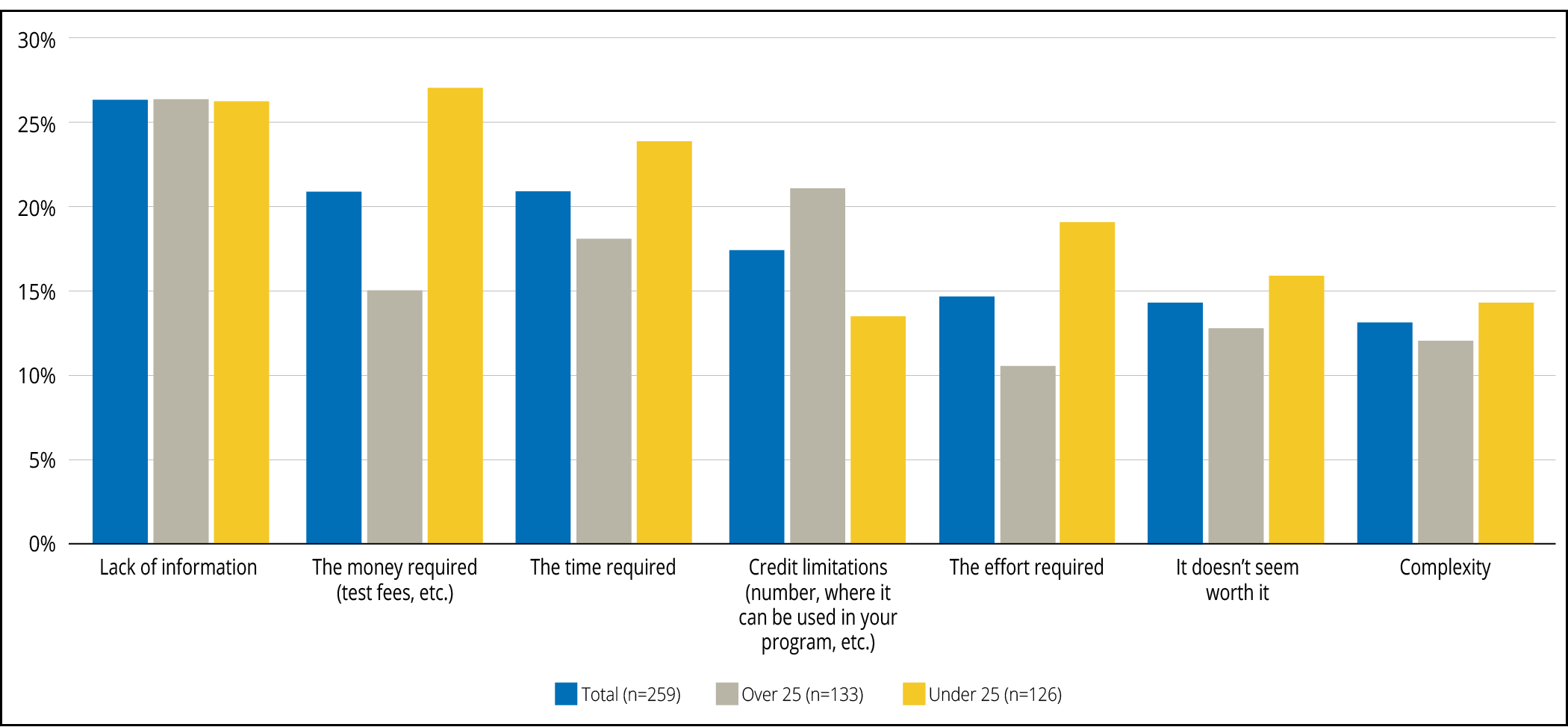

- Students cited lack of information about PLA as a top barrier to accessing PLA. Adult learners cited money and time required with more frequency than younger students. Younger students cited credit limitations (such as number of credits eligible, how/if a student can apply the credits to their program of study) at a higher rate than older students.

Briana, an African American female in her twenties is stationed on an Air Force base in Southwestern United States. [1] Upon graduating from high school, she knew she did not want to go to college right away, if at all. So based on the recommendation of a family friend, she enlisted in the Air Force. For the last seven years, she has worked in a human resources capacity on several bases. Briana says that it is common knowledge in the military that you can get college credit for military experiences, trainings, and by completing CLEP and DANTES exams. She hopes to get a civilian job in human resources when her current enlistment ends in two years. Briana believes she can get a better job if she has a college degree, so she enrolled part time in an online bachelor’s degree program. Through the education office on base and the academic advisor she was assigned on campus, she has figured out how to get college credit for CLEP exams and the Airman Leadership training and Tech School training she has completed in the military. She appreciates the opportunity to earn credit for knowledge and skills gained in the military and appreciates the lower cost of obtaining a degree. However, she has found it challenging to piece together the advice from the military education office and her college the advisor. She wonders in what ways advisors across sectors might be able to work together to better support military students.

Introduction

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and related recession, millions of Americans are facing temporary and permanent job loss in 2020 and beyond, and they will be looking to reskill and upskill to re-enter the workforce. Just like Briana, many workers have acquired college-level learning on the job or elsewhere and can earn credit for this learning through a process called Prior Learning Assessment (PLA).

Research shows that PLA can help students complete their degree or credential and save time and money while doing so.[2] A new study released by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) and the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL), used propensity score matching to isolate the impact on credential completion from PLA alone. The research found that PLA increased the likelihood of an adult student’s completion by more than 17 percent. The impact of PLA on credential completion was also significant for students historically underrepresented in higher education:

- Completion rates for Hispanic students increased 24 percent

- Completion rates for Black students increased 14 percent

- Completion rates for Pell recipients increased 19 percent.[3]

These findings suggest that PLA can be an important tool for helping students leverage what they already know and can do and apply that learning toward a postsecondary credential. PLA can certainly play a strong role in helping workers that have been displaced due to the COVID-related recession receive the education they need to enter and re-enter the workforce.[4]

Yet, among the 72 institutions participating in the CAEL/WICHE study, the proportion of adult students who take advantage of PLA is small – just over 10 percent of the adult students in this sample had earned credit from PLA.[5] Multiple research studies in the last few years have also reported low numbers of students earning PLA credits (between two and ten percent).[6] In order for PLA programs and policies to be effective, many more students need to be aware of and encouraged to take advantage of PLA.

The other briefs written in this series, with input from policymakers, system leaders, and institution administrators and practitioners, offer suggestions on what more colleges and universities could and should be doing to make PLA more accessible to students.[7] This brief brings attention to the student perspective, for these are the very individuals PLA programs and policies are meant to serve. Through interviews and surveys, current college students share the types of credit-eligible prior experiences that resulted in recognizable knowledge, how they learned of PLA, what benefits they gained by earning PLA credit, challenges they faced, and offer recommendations to institutions in this brief. Doing so can help more of them finish what they start and finish more quickly.

Methods

This brief draws on data from two sources. The first source is a survey developed and deployed by WICHE and the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) to current undergraduate students across the country using Qualtrics panel program as part of AACRAO’s investigation into the relationship between registrars and PLA.[8] The survey asked students about their prior learning experiences, access to and use of prior learning assessment programs, and their perspectives about their experiences. In all, 1,184 students responded to the survey.

Demographics of WICHE/AACRAO Survey Respondents

- Gender: 55 percent of survey respondents identified as female, 43 percent as male, and 1.6 percent preferred not to self-identify.

- Age: 55 percent of the respondents were under 25 years old, 32 percent were between 25 and 34 years old, and 13 percent were 35 years old or older.

- Ethnicity: 17 percent identified as Hispanic or Latino.

- Race: 71 percent of survey respondents identified as White, 18 percent identified as Black, 8 percent identified as Asian, 5 percent identified as American Indian/Alaska Native, and less than 1 percent identified as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (students were encouraged to check all the ethnicities with which they identify).

- College enrollment: two thirds of the students were enrolled in four-year institutions; one third were enrolled in a community or technical college. The majority of the community college student respondents were older than 25.

The second source of data for this brief is an interview protocol designed by WICHE and CAEL to further capture the student experience regarding PLA as part of the CAEL/WICHE PLA Impact study. Six students who had earned credit for their prior learning across four public institutions were interviewed.[9] The interview protocol asked students about their background, their previous work and college experience, their future career and education goals, and their experience with and perspectives on PLA.

Demographics of WICHE/CAEL Student Interviewees

- The six students ranged in age from 24-60.

- Three students identified as white and female, one student identified as a while male, one student identified as a Black female, and one identified as a Latina.

- Four students had enrolled in college just after high school but stopped out citing money, time, and life circumstances.

- Students were equally enrolled in associate and bachelor’s degree programs.

- Four students had worked for the same company for several years. Two were lifetime employees of their respective companies before the companies folded in 2017 or 2018.

- Two students had military experience.

Findings

In the following section, answers to several questions about the student experience related to PLA are provided.

What is Prior Learning Assessment

Many students – as well as potential students – have acquired a great deal of college-level knowledge and skills through their day-to-day lives outside of academia: from work experience, on-the-job training, formal corporate training, military training, volunteer work, self-study, and myriad other extra-institutional learning opportunities available through low-cost or no-cost online sources.

The process for recognizing and awarding credit for college-level learning acquired outside of the classroom is often referred to as Prior Learning Assessment (PLA). There are several ways students can demonstrate this learning and earn credit for it in college. The various partners involved in creating this series of briefs are examining different types of PLA and using the following general descriptions of the different methods.

- Standardized examination: Students can earn credit by successfully completing exams such as Advanced Placement (AP), College-Level Examination Program (CLEP), International Baccalaureate (IB), Excelsior exams (UExcel), DANTES Subject Standardized Tests (DSST), and others.

- Faculty-developed challenge exam: Students can earn credit for a specific course by taking a comprehensive examination developed by campus faculty.

- Portfolio-based and other individualized assessment: Students can earn credit by preparing a portfolio and/or demonstration of their learning from a variety of experiences and non-credit activities. Faculty then evaluate the student’s portfolio and award credit as appropriate.

- Evaluation of non-college programs: Students can earn credit based on recommendations provided by the National College Credit Recommendation Service (NCCRS) and the American Council on Education (ACE) that conduct evaluations of training offered by employers or the military. Institutions also conduct their own review of programs, including coordinating with workforce development agencies and other training providers to develop crosswalks that map between external training/credentials and existing degree programs.

What types of prior learning experiences do students have?

When asked what types of prior learning students have, the majority of students who completed the survey or interview cited their work experience.

Survey respondents

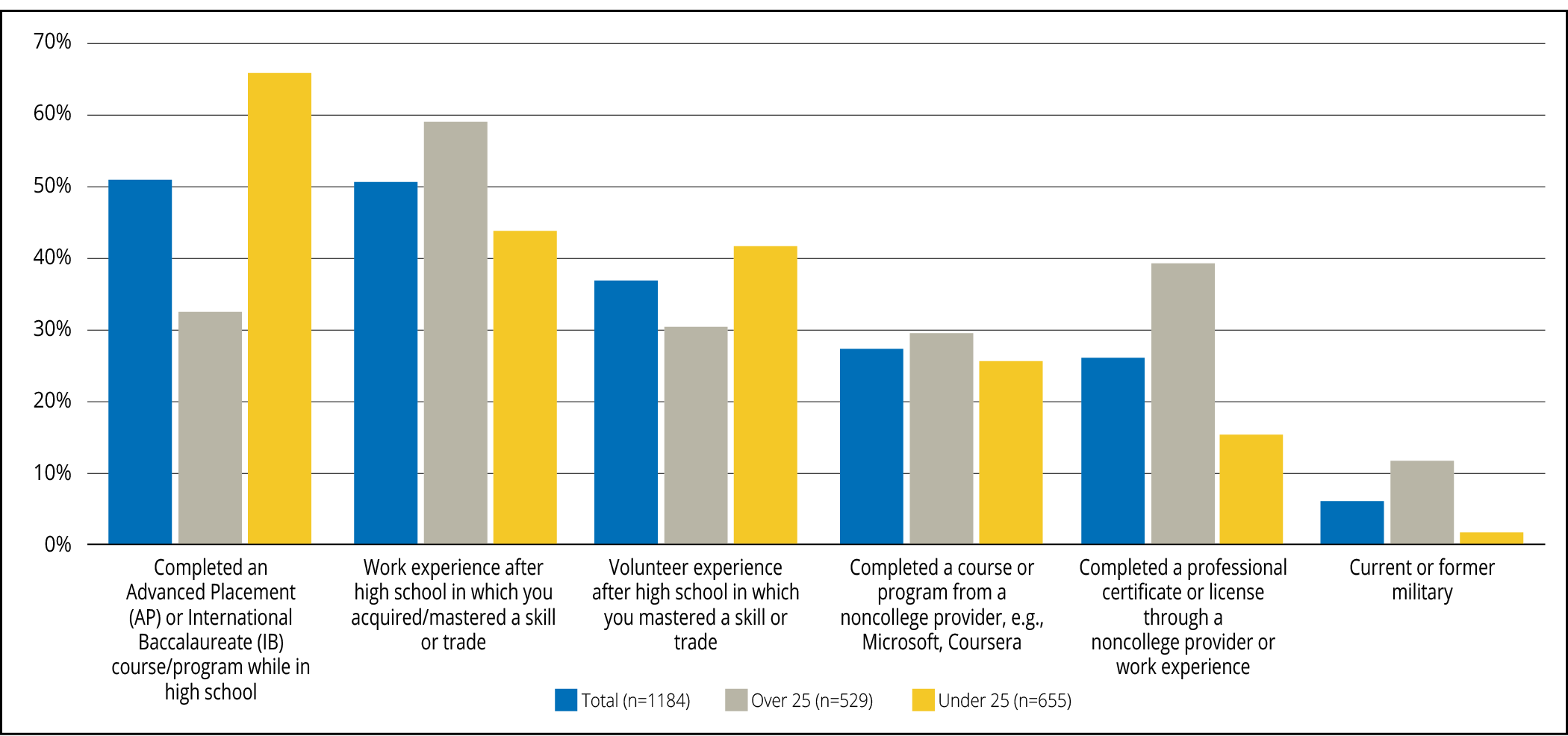

Students responding to the survey were encouraged to select all credit-eligible experiences that applied to them (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Types of Prior Learning Outside the Traditional Classroom

Half of the students reported having work experience or having taken an AP or IB exam. Adult learners (ages 25 and older) were more likely to report having work experience, completing a certificate or professional license, completing a course from a non-college provider, or their enlistment in the military. Students under the age of 25 were more likely to report having taken an AP/IB course or had volunteer experience.

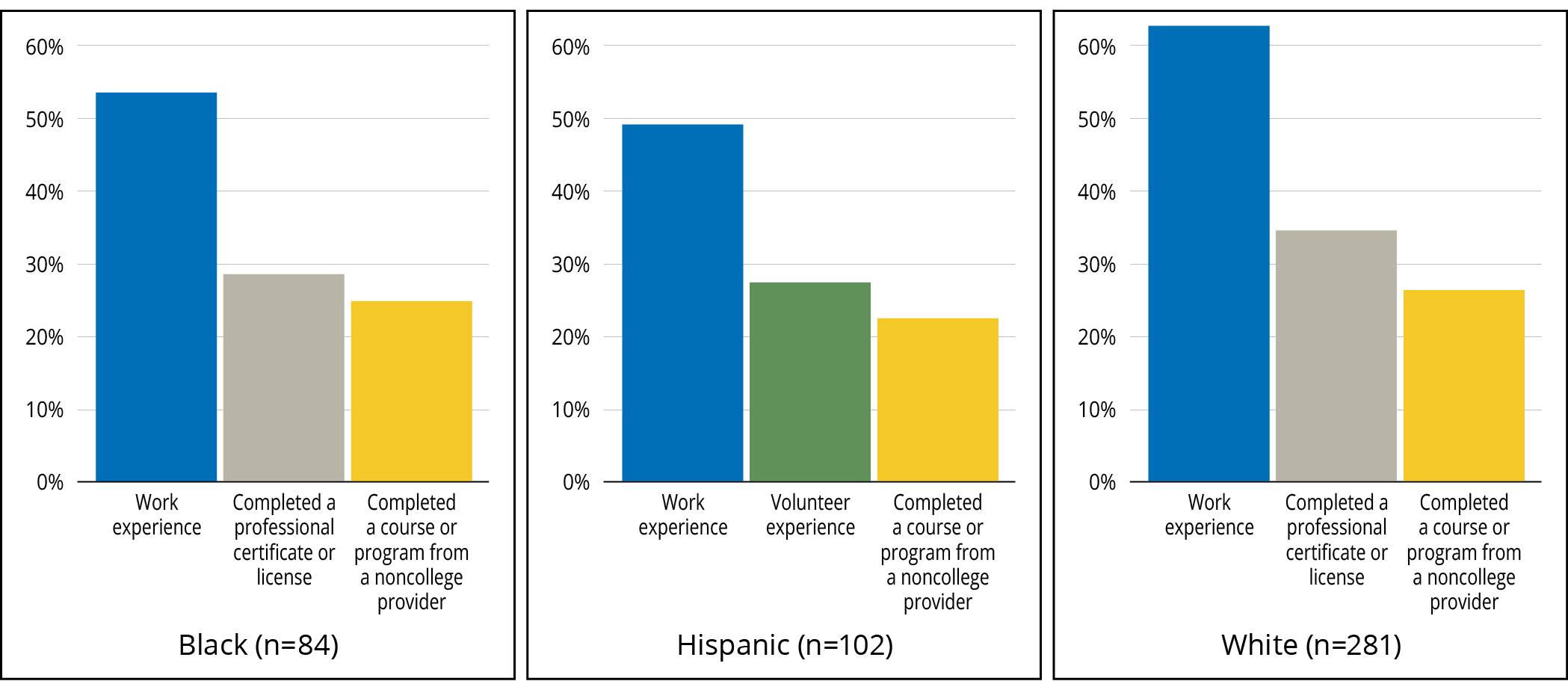

Figure 2 shows the most common types of experiences that could be considered for PLA credit if the student were to demonstrate college-level learning for adult students (ages 25 and older) by race/ethnicity.[10]

Figure 2. Top Three Types of Prior Learning Outside the Traditional Classroom by Race/Ethnicity

Regardless of race/ethnicity, the most common experience (that could potentially help students earn PLA credit if they demonstrate college-level learning) cited by adult students was work experience. Hispanic students also reported volunteer experience.

Interviewees

The students we interviewed all had work experience. Some had completed a professional certificate or military training. One individual had completed hazmat training and forklift training as part of his career working in a chemical plant. Another individual completed an Airman Leadership Program and Tech School while in the military. A third individual worked in a hospital as a patient advocate and used her experiences working in the emergency room and billing office to complete a portfolio. None reported earning AP/IB credit from high school.

These results, while not necessarily fully representative of all students, underscore that prior learning and knowledge are gained in a variety of ways.

How do students learn about and access PLA?

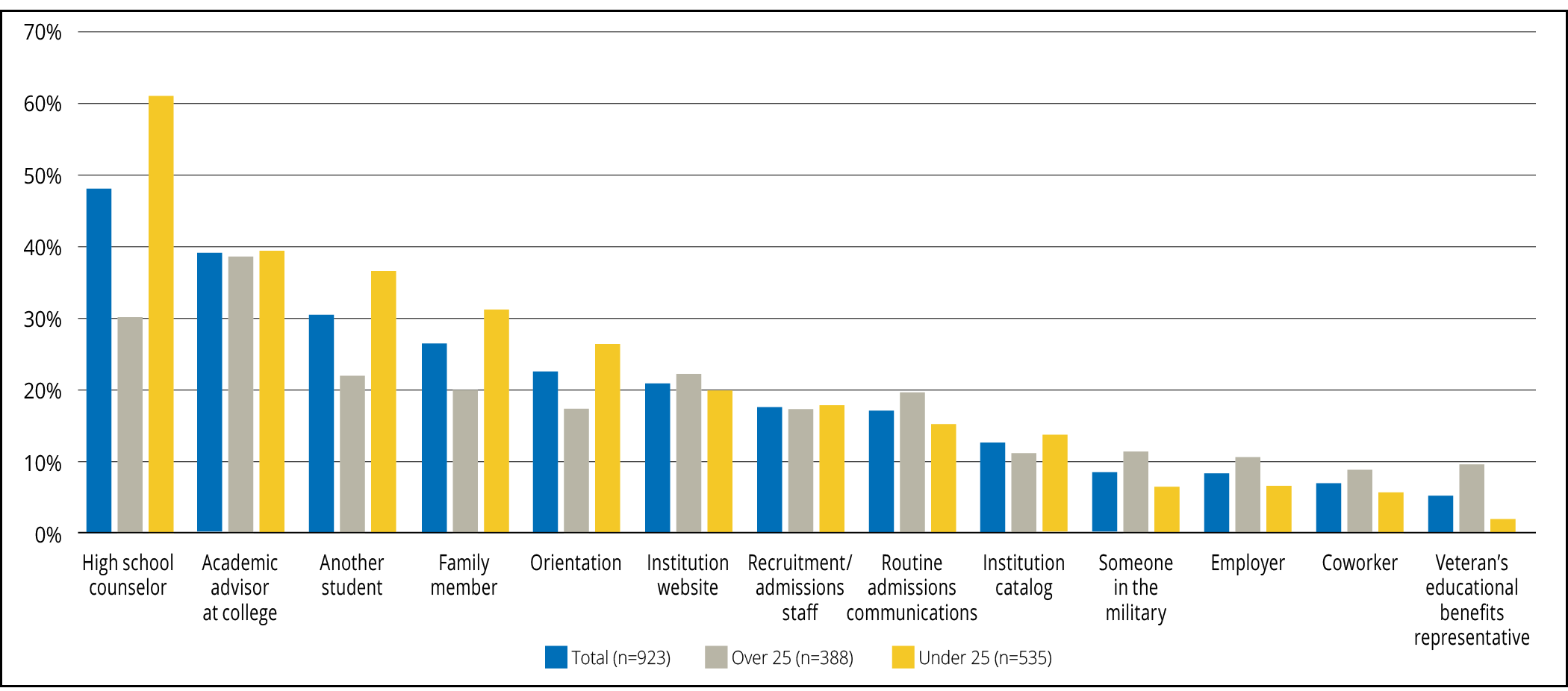

Accrediting bodies encourage (or even require) institutions with PLA opportunities to make these opportunities known to students.[11] And as of July 1, 2020, the U.S. Department of Education requires that institutions with PLA opportunities publish “written criteria used to evaluate and award credit for prior learning experience.”[12] When asked how students knew about the opportunity to earn credit for their prior learning/experiences, few students reported learning about PLA through written announcements. Rather, survey respondents and interviewees both suggested that personalized conversations with individuals are most influential.

Survey respondents

Among the survey respondents, high school counselors, academic advisors on the college campus, other students, or a family member were the four most commonly cited PLA resources. Older students and students attending a community college indicated that they learned about PLA from their employer, a coworker, or someone in the military at slightly higher rates than their peers who were younger and who were attending four-year institutions (See Figure 3).

Figure 3. Means of Learning about PLA

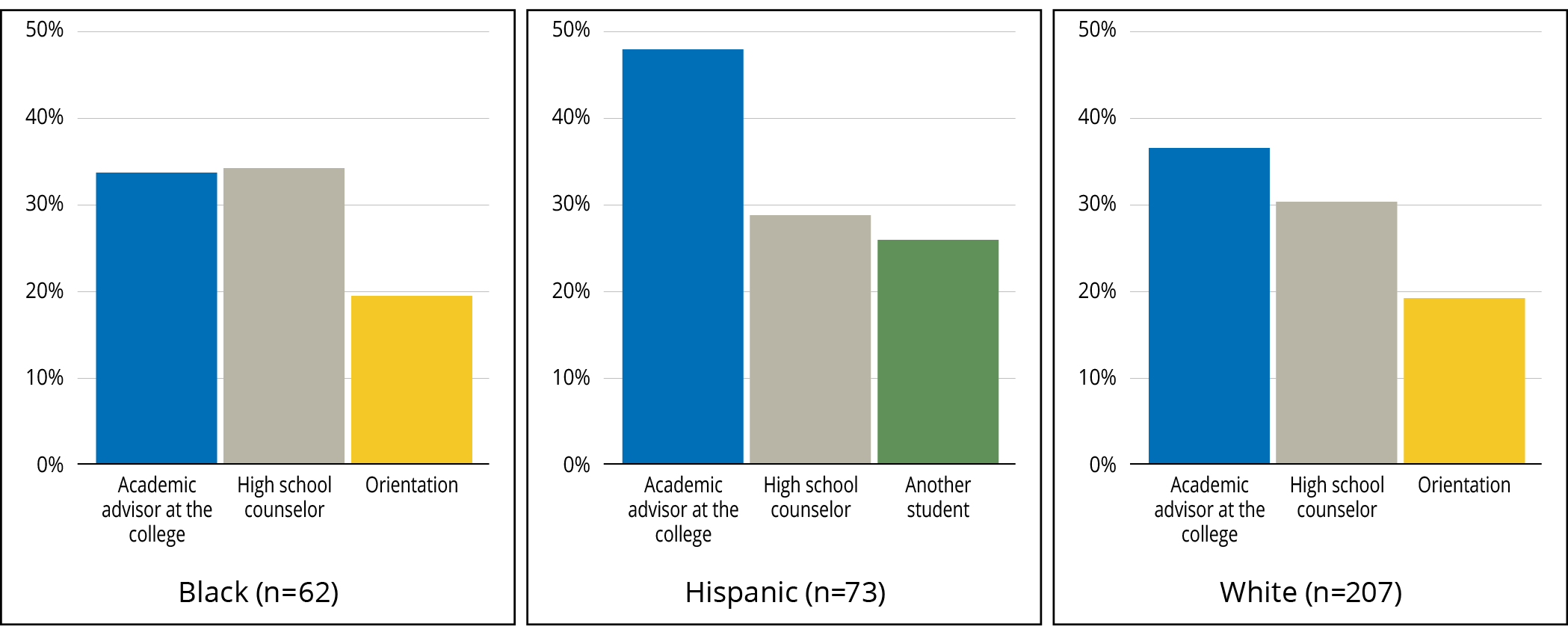

Figure 4 shows the most common means of learning about PLA for adult students (ages 25 and older) by race/ethnicity.

Figure 4. Top Three Means of Learning about PLA by Race/Ethnicity

Regardless of race/ethnicity, the most commonly cited source of PLA knowledge for adult students was academic advisors.

Interviewees

The majority of students interviewed reported learning about PLA from individual meetings with their academic advisor once enrolled in college. Two learned about prior learning from programs for displaced workers funded by the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act that their companies partnered with when the companies were shutting down in response to the COVID pandemic. Two students reported learning about PLA through a coworker or fellow service member. Only one student reported learning about PLA through a nonpersonal connection: she received a marketing email shortly after enrolling at her institution that told her she could potentially earn credit for work experience.

Importantly, the students in these studies report learning about PLA from personal connections with individuals. The method of advertising PLA that seems least used by students is when it is written in the college catalogue. This suggests that the state, federal, and accreditor policies that say PLA opportunities need to be made transparent and available via writing to students, are not adequate to reach students. Human connection is important for helping students learn about PLA.

What benefits do students see to earning PLA?

Several studies in addition to the CAEL/WICHE PLA Impact study suggest students benefit from PLA in terms of degree completion, reduced time to degree, and cost savings.[13] When asked what benefits students found from earning PLA, the majority of students confirmed benefits to their college trajectory. Several students also reported benefits to their careers.

Survey respondents

Respondents reported the most popular benefits were related to educational benefits (such as shortening the time to a degree). Perhaps unsurprisingly, adult learners indicated PLA credit benefited them in their professional careers more so than their younger peers, while younger students indicated that this credit benefited them in their college career more so than their older peers (See Figure 5).

Figure 5. Benefits to Earning PLA Credit

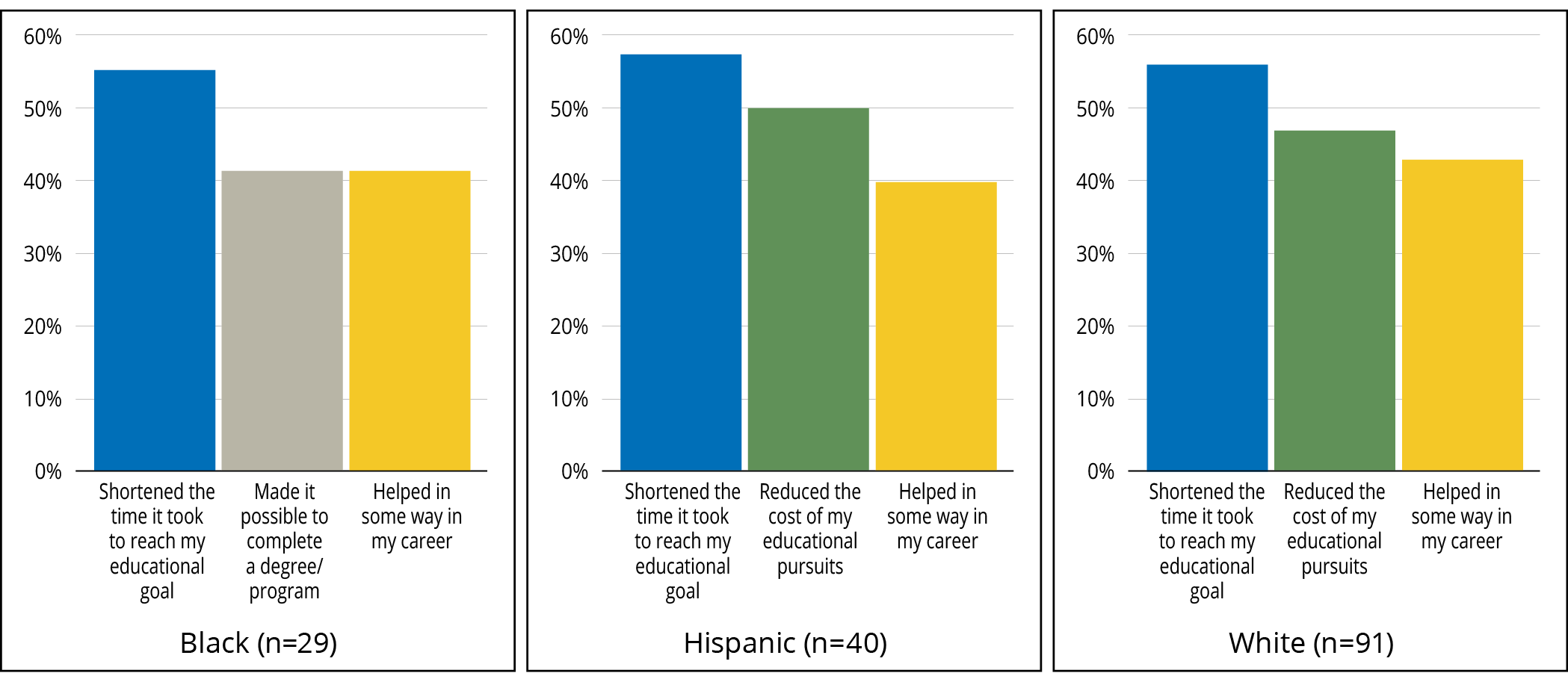

Figure 6 shows the most common benefits of PLA reported by adult students by race/ethnicity.

Figure 6. Top three benefits of earning PLA credit by race/ethnicity

Regardless of race/ethnicity, adult learners reported that earning PLA credits benefited them by shortening the time it took for them to reach their educational goal and helped them in their career.

Interviewees

Student interviewees reported earning PLA helped them in their college career by “being able to radically reduce [tuition].” Earning PLA credits also allowed students to continue working while attending school: “I was working two jobs at the time … so the [portfolio] … let me save money and time and continue working and not have to take time off of work.” Several students who earned PLA through portfolio assessment reported the experience helped them reflect on what they learned: “Whenever you have a job, sometimes you don’t really think about what you’re doing, you don’t really consider what you’re learning in the process of doing it.”

While the student interviewees did not say how PLA helped them explicitly in their professional careers, many of them suggested earning a degree helped them in their professional career; and earning PLA credits was a key factor in them getting that degree.

The students in these studies confirm prior research that suggest students benefit from PLA in terms of helping them complete a degree or credential in less time and for less money. Importantly, these students also speak to the value they see in PLA in terms of employment and career advancement.

Sam,[14] a white male in his fifties, lives in a small Appalachian town. After high school, he enrolled in college and began working as a laborer in a factory. After working and earning 70 college credits, he stopped out of school because he began working more and more hours. Over the next 25 years, he worked his way up through the same chemical plant. When the plant closed in 2018, he hoped to find a job as a manager for a large warehouse or transportation company but realized that unless you “grow up” in a company as he had, or have a college degree, few, if any, companies would hire at the manager level. So, he chose to take advantage of a federal dislocated worker program that would pay for two years of college for him and his colleagues because his plant closed. He enrolled in a local community college to earn an associate’s degree in transportation management. Upon enrollment, he met with a college advisor, who helped him earn college credit for the certificates in Hazardous Materials and Forklift Operations he received on the job. Although he was able to only apply these credits as elective credits toward his degree, he questions if he actually had more applicable skills in management that he had learned on the job that could have been converted to credits that would apply to his major. He was left wondering if his path through college could have been expedited if his advisor had looked at his resume in addition to asking what types of credentials he earned on the job.

What challenges do students face when attempting to earn PLA?

Multiple research studies in the last few years have reported low numbers of students earning PLA credits (between two and ten percent).[15] Hearing from students themselves on perceived challenges and barriers to accessing and using PLA can help us to understand why there might be such a low up-take up rate in PLA.

When asked why students chose not to attempt to earn credit for their prior experiences, or what challenges they faced if they did attempt to earn credit, both the survey respondents and interviewees cited lack of information, time, and limits to how their PLA credits could be used. Survey respondents also reported cost as a barrier.

Survey Respondents

Roughly one-third of survey respondents knew there was the possibility of earning credit for their experiences and learning outside of the classroom, yet they chose not to attempt to seek college credit for those experiences (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Barriers to PLA

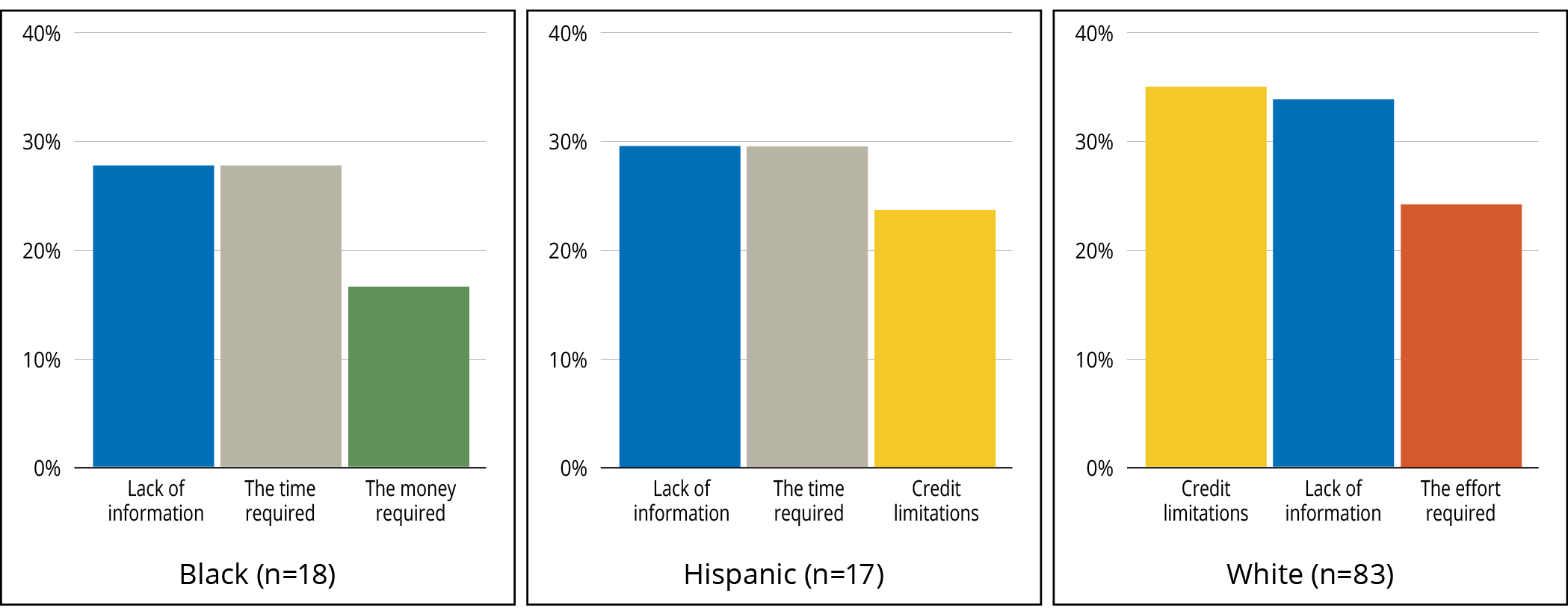

Regardless of age and race/ethnicity, lack of information about PLA was cited as the top barrier. Adult learners cited money and time required with more frequency than younger students. Younger students cited credit limitations (such as number of credits eligible, how/if a student can apply the credits to their program of study) at a higher rate than older students.

Figure 8 shows the most common benefits of PLA reported by adult students by race/ethnicity. Because of small cell sizes, it was only possible to disaggregate data for adult learners for students who identified as Black, Hispanic, or White.

Figure 8. Top Three Barriers to PLA by Race/Ethnicity

Student Interviewees

Although all the interviewees successfully accessed PLA opportunities, they talked about challenges faced: a couple of students alluded to challenges regarding credit limitations: “I actually think…[my PLA credits] weren’t counted towards, towards my degree because I have other science classes that are more relevant.” And one student worried about missing out on information she could learn if she took the class rather than tested out of it. Several students commented on the challenges of preparing portfolios: “Obviously I’ve had a lot of experiences in life. But how do you put that into words and then submit that to someone else?”

Adult learners, especially those who are looking to reskill or upskill because of the economic impact of COVID-19 often do not have time or money to invest in their education if it isn’t going to help their end goal. As stated by an adult learner who didn’t attempt to earn credit for his/her prior learning in an open-ended survey response, “I think just more information about the process and what is required [would have been helpful]. I just am fearful of going through a process to be told it doesn’t apply.” While some students talked about cost savings in terms of tuition as a benefit to PLA, other students who relied on financial aid to fund their education found PLA fees a barrier. In order to serve students equitably, barriers to PLA need to be addressed.

Recommendations

Findings from the student survey and student interviews offer several recommendations for institutions and policymakers to better serve students attempting to earn credit for prior experiences.

- Provide information about PLA to students early and often, and in multiple formats. Several students recommended that institutions tell students immediately upon enrollment about the opportunity to earn credit for prior learning. One student interviewed thought “it might be too late” if students only learn about this opportunity later in their college career. Indeed, one student surveyed reported, “If I had learned about CLEP tests before taking my basic classes I would have used them but I was unaware.” Another surveyed student who did not attempt to earn PLA credit reported that while “[earning credit for] life work experience was discussed” during orientation, at the time “it sounded too complicated to pursue [and] it was never mentioned again.”

- Offer individualized, holistic advising regarding PLA. Many students interviewed suggested that institutions should connect students to an individual academic advisor who will take the time to learn about the education and employment history of each student. One survey respondent who did not attempt to earn PLA credit suggested that having “someone guiding me through the process” would have helped him attempt to earn PLA credits. Another survey respondent pointed to the need for institutions to proactively offer advising to students regarding PLA, “[I needed] more information on the process and who to go to for help.”

- Coordinate services regarding PLA. A couple of students interviewed recommended that institutional advisors working with active military personnel or displaced workers should attempt to connect with education office staff on base or former employers if possible. One student reported having to go back and forth between the education office on base and her advisor at the institution and figure out how to “crosswalk” the different information.

- Reduce the cost of PLA through financial aid. Currently, federal financial aid cannot be applied to fees related to PLA and only one state allows students to use state financial aid dollars towards PLA costs.[16] Thus, for students funding their education through financial aid, PLA is an additional cost rather than a way to reduce their total cost of education. Indeed, one student surveyed who did not attempt to earn college credit for prior learning reported that the process “costs money that I don’t have.”

These student-led recommendations echo many of the recommendations made by organizations conducting original research on PLA practices as part of the Recognition of Learning brief series and those found in the new report released by CAEL and WICHE, The PLA Boost: Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes. By following through with these recommendations, institutions and policymakers can make a positive impact on student success and better support students who come to campus with college-level learning acquired outside of the classroom.

In addition to supporting students through improved PLA policies and practices, institutions can also increase their tuition revenue. CAEL and WICHE found that students with PLA credits enrolled in about 18 additional credit hours than their peers without PLA credit.[17] For example, one student interviewed mentioned that earning PLA credit “encouraged me to continue on in school … initially I was discouraged because I needed to take all of these electives.”

Conclusion

Across the series of briefs written as part of the Recognizing Prior Learning in the 21st Century initiative, the impact that PLA can have on student success is clear. Whether it’s from the perspective of the registrar, the student advisor, administrators on the community college or four-year campus, or the student, issues around marketing, advising, coordinating services across campus (and other providers), and financial aid come up in regard to improving policies and practices related to prior learning. While these are not the only areas institutions and states should consider addressing when developing or improving PLA policies and practices, from the student perspective, they are a good place to start.

Endnotes

[1] To protect the privacy of these students, names, ages, and other identifying information have been changed slightly.

[2] Rebecca Klein-Collins, Jason Taylor, Carianne Bishop, Peace Bransberger, Patrick Lane, and Sarah Leibrandt, The PLA Boost: Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes (Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, October 2020), accessed on 1 November 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/PLA-Boost-Full-Report-CAEL-WICHE-Oct-2020.pdf.

[3] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[4] Sarah Leibrandt, Rebecca Klein-Collins, and Patrick Lane, Recognizing Prior Learning in the COVID-19 Era: Helping Displaced Workers and Students One Credit at a Time (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, June 2020), accessed on 3 September 2020, at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/pla-covid-19/.

[5] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

[6] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost; Alexei Matveev, “Survey of Non-Credit to Credit Conversion Activities: Key Highlights,” PowerPoint presentation, Connecting Credentials Presentation, Atlanta, GA, 2018; Li Kuang and Heather McKay, Prior Learning Assessment and Student Outcomes at the Colorado Community College System (Piscataway, NJ: Education and Employment Research Center, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, December 2015), accessed on 1 June 2020, at https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/documents/PLA Baseline Report FINAL 2-4-16.pdf.

[7] Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, “Recognition of Learning,” accessed on 23 September 2020, at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/.

[8] Kilgore, Wendy, An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, July 2020), accessed on 28 July 2020, at https://www.wiche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aacrao-brief071420.pdf.

[9] We reached out to a subset of the 72 institutions that participated in the CAEL/WICHE impact study to conduct staff and student interviews. These institutions varied by sector, geographic location, and size. We asked the PLA coordinator at each institution to connect us to one or two current students who had earned PLA. Students volunteered to participate in interviews and received $50 gift cards for their time.

[10] Because of small cell sizes, it was only possible to disaggregate data for adult learners (age 25 and older) who identified as Black, Hispanic, or White.

[11] Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, Holding Tight or at Arm’s Length: How Higher Education Regional Accrediting Bodies Address PLA (Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2014); Rosa Garcia and Sarah Leibrandt, The Current State of Prior Learning Policies (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, November 2020), accessed on 15 November 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/pla-policies/.

[12] Section 668.43 (c)(11)(iii) from Federal Registrar, The Daily Journal of the United States Government, Rule, “Student Assistance General Provisions, The Secretary’s Recognition of Accrediting Agencies, The Secretary’s Recognition Procedures for State Agencies, 1 November 2019,” accessed on 10 August 2020, at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/11/01/2019-23129/student-assistance-general-provisions-the-secretarys-recognition-of-accrediting-agencies-the; Garcia and Leibrandt, The Current State of Prior Learning Policies.

[13] Walter Stephen Pearson, Enhancing Adult Student Persistence: The Relationship between Prior Learning Assessment and Persistence Toward the Baccalaureate Degree (Ames, IA: Iowa State University, 2000); Rebecca Klein-Collins, Fueling the Race to Postsecondary Success: A 48-Institution Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes (Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2010), accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://www.cael.org/pla/publication/fueling-the-race-to-postsecondary-success; Brent Sargent, An Examination of the Relationship Between Completion of a Prior Learning Assessment Program and Subsequent Degree Program Participation, Persistence, and Attainment (Sarasota, FL: University of Sarasota, 1999); Heather McKay, Renee Edwards, and Suzanne Michael, Colorado Helps Advanced Manufacturing Program Final Report (Piscataway, NJ: Education and Employment Research Center, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, September 2017), accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Centers/champ_final_report.pdf.

[14] To protect the privacy of these students, names, ages, and other identifying information have been changed slightly.

[15] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost; Matveev, “Survey of Non-Credit to Credit Conversion Activities”; Kuang and McKay, Prior Learning Assessment and Student Outcomes.

[16] Garcia and Leibrandt, The Current State of Prior Learning Policies.

[17] Klein-Collins, Taylor, Bishop, Bransberger, Lane, and Leibrandt, The PLA Boost.

References

Council for Adult and Experiential Learning. Holding Tight or at Arm’s Length: How Higher Education Regional Accrediting Bodies Address PLA. Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2014.

Garcia, Rosa and Sarah Leibrandt. The Current State of Prior Learning Policies. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, November 2020. Accessed on 15 November 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/pla-policies/.

Kilgore, Wendy. An Examination of Prior Learning Assessment Policy and Practice as Experienced by Academic Records Professionals and Students. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, July 2020. Accessed on 28 July 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/aacrao-brief071420.pdf.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca, Jason Taylor, Carianne Bishop, Peace Bransberger, Patrick Lane, and Sarah Leibrandt. The PLA Boost: Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes. Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, October 2020. Accessed on 1 November 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/PLA-Boost-Full-Report-CAEL-WICHE-Oct-2020.pdf.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca. Fueling the Race to Postsecondary Success: A 48-Institution Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2010, accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://www.cael.org/pla/publication/fueling-the-race-to-postsecondary-success.

Leibrandt, Sarah, Rebecca Klein-Collins, and Patrick Lane. Recognizing Prior Learning in the COVID-19 Era: Helping Displaced Workers and Students One Credit at a Time. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, June 2020. Accessed on 3 September 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/pla-covid-19/.

McKay, Heather, Renee Edwards, and Suzanne Michael. Colorado Helps Advanced Manufacturing Program Final Report. Piscataway, NJ: Education and Employment Research Center, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, September 2017. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://smlr.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/documents/Centers/champ_final_report.pdf.

Pearson, Walter Stephen. Enhancing Adult Student Persistence: The Relationship between Prior Learning Assessment and Persistence Toward the Baccalaureate Degree. Ames, IA: Iowa State University, 2000.

Sargent, Brent. An Examination of the Relationship Between Completion of a Prior Learning Assessment Program and Subsequent Degree Program Participation, Persistence, and Attainment. Sarasota, FL: University of Sarasota, 1999.

Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. “Recognition of Learning.” Accessed on 23 September 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/.

About the Author

- Sarah Leibrandt is a senior research analyst at the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. Since joining WICHE in 2013, Leibrandt has helped state agencies share education and workforce data with each other through the Multistate Longitudinal Data Exchange as a way to provide better information to students and their families while also improving education, workforce, and economic development policy. Currently, Leibrandt leads WICHE’s adult learner initiatives that include Recognizing Learning in the 21st Century, a large-scale research study and landscape analysis of the scaling of prior learning assessment policies and practices. Prior to joining WICHE, Leibrandt worked for the Colorado Department of Education and Red Rocks Community College. Leibrandt earned a bachelor’s degree from Wellesley College and a Ph.D. in Education Policy from the University of Colorado Boulder.

About the organization

- For more than 65 years, the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE) has been strengthening higher education, workforce development, and behavioral health throughout the region. As an interstate compact, WICHE partners with states, territories, and postsecondary institutions to share knowledge, create resources, and develop innovative solutions that address some of our society’s most pressing needs. From promoting high-quality, affordable postsecondary education to helping states get the most from their technology investments and addressing behavioral health challenges, WICHE improves lives across the West through innovation, cooperation, resource sharing, and sound public policy.

Copyright

Copyright © 2020 by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education

3035 Center Green Drive, Boulder, CO 80301-2204

An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer

Printed in the United States of America

Publication number 4a500134

Disclaimer

This publication was prepared by Sarah Leibrandt of the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Lumina Foundation, its officers, or its employees, nor do they represent those of Strada Education Network, its officers, or its employees.