Recognition of Learning TOC

Key Highlights of this Brief

- Most HBCUs advertise PLA opportunities on their websites and have policies to grant PLA credits

- Some public HBCUs target military-based PLA credits, especially institutions that have relationships with military bases

- HBCU students utilize CLEP in their senior years to gain credits that facilitate fulfilling graduation requirements

- Equity issues prevent incoming HBCU students from gaining PLA credit through high school based programs such as Advanced Placement (AP) and International Baccalaureate (IB)

- Historic HBCU underfunding by states leads to lack of training, facilities maintenance, and personnel training that would support student recruitment and PLA credit engagement

Introduction

“Before I chose Voorhees College, I went to several other institutions — Denmark Tech, Allen University and South Carolina State University. I had a lot of credits and courses from these institutions. I wanted to major in Business Administration and was able to come in as a sophomore. Two years later, I was informed that one of my general education courses did not transfer. My advisor told me about CLEP. I took the test and passed and as a result I received course credit. I am on track to graduate in May 2020 and I will be the first person in my family to graduate. My goal is to open a non-profit and always help kids who need mentoring.”

– Voorhees College Senior, Business Administration Major

Created in the 19th century primarily to provide education and training to free persons of African descent, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) focused on practical training that facilitated the ability to earn a living. Today, the 101 public and private HBCUs continue to serve the African American community, with 85 percent of HBCU students being African American. HBCUs also continue to foster economic opportunity through educational attainment for low-income students.

One way in which HBCUs might improve education outcomes for their students is through the development and implementation of prior learning assessment (PLA) policies and practices. PLA is the process for evaluating and awarding credit for college-level learning that has been acquired outside of the classroom through work and life experience. It has long been known that PLA has a positive correlation with student persistence in higher education,[1] higher graduation rates,[2] and shorter times to degree attainment for non-traditional students.[3]

Yet, to date, there has been no research done on the types of PLA offered at HBCUs and student outcomes related to PLA. This brief fills this gap by exploring the ways in which HBCUs acknowledge and award postsecondary credit to students like the one attending Voorhees College for college-level learning that took place outside of the institution as a way to improve student outcomes. To do so, Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF) undertook research that reviewed information publicly available regarding PLA policies and information on HBCU websites. The research also engaged in a more in-depth case study analysis of four targeted HBCUs, each of which represents a distinct type of institution. This brief concludes with recommendations for policy and practice with regard to HBCUs and other institutions facing similar resource constraints.

Types of Prior Learning Assessment

Many students – as well as potential students – have acquired a great deal of college-level knowledge and skills through their day-to-day lives outside of academia: from work experience, on-the-job training, formal corporate training, military training, volunteer work, self-study, and myriad other extra-institutional learning opportunities available through low-cost or no-cost online sources.

The process for recognizing and awarding credit for college-level learning acquired outside of the classroom is often referred to as Prior Learning Assessment (PLA). There are several ways students can demonstrate this learning and earn credit for it in college. The various partners involved in creating this series of briefs are examining different types of PLA and using the following general descriptions of the different methods.

- Standardized examination: Students can earn credit by successfully completing exams such as Advanced Placement (AP), College-Level Examination Program (CLEP), International Baccalaureate (IB), Excelsior exams (UExcel), DANTES Subject Standardized Tests (DSST), and others.

- Faculty-developed challenge exam: Students can earn credit for a specific course by taking a comprehensive examination developed by campus faculty.

- Portfolio-based and other individualized assessment: Students can earn credit by preparing a portfolio and/or demonstration of their learning from a variety of experiences and non-credit activities. Faculty then evaluate the student’s portfolio and award credit as appropriate.

- Evaluation of non-college programs: Students can earn credit based on recommendations provided by the National College Credit Recommendation Service (NCCRS) and the American Council on Education (ACE) that conduct evaluations of training offered by employers or the military. Institutions also conduct their own review of programs, including coordinating with workforce development agencies and other training providers to develop crosswalks that map between external training/credentials and existing degree programs.

While PLA is often discussed as a strategy to help returning adult students who have work experience, the methods most commonly used among HBCUs (pre-college test-based assessments, military-based credit, or knowledge/experience-based assessment) are not available to all students, particularly to those who are older. Military credits are available only to active military service members and veterans, and credit for AP/IB is generally available only to high school students. TMCF was guided in its PLA definition used throughout this brief by the HBCUs themselves, so this brief highlights only certain methods. Other briefs in this series generally focus less on types of PLA credit earned through high school programs and more on those aimed at adult learners. However, the inequitable access to AP and IB courses (and resultant credit) is a central issue for students at HBCUs (and for underrepresented students in general) and deserves further study and focus in discussions about PLA.

Background on HBCUs

HBCUs are defined as institutions of higher education that were established prior to 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of Black Americans. HBCUs primarily serve low-income students and first-generation college students who come from underserved communities, whether urban or rural. HBCUs were founded to educate the least-resourced individuals, free-born people of African descent (for instance, Cheyney University in Pennsylvania), and former slaves. Cheyney University in Pennsylvania, America’s first HBCU, was founded in 1837 as the “Institute for Colored Youth.” In 1851, the Miner Normal School – today’s University of the District of Columbia – was established as a school for African American women. The Ashmun Institute was founded in 1854 in Pennsylvania (Lincoln University), and in 1856, Wilberforce University was founded by the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Wilberforce, Ohio – the first HBCU owned and operated by African Americans. LeMoyne-Owen College was opened in Memphis, Tennessee in 1862.

Predominantly Black Institutions of Higher Education (PBIs) were founded after 1964. PBIs have at least 1,000 undergraduate students, of which not less than 50 percent are low-income or first-generation to attend college, and whose student body is composed of at least 40 percent Black students, and of which not less than 50 percent are in a baccalaureate program. Today, there are 101 HBCUs and PBIs (called HBCUs for the remainder of the chapter). Of these institutions, 89 are four-year public or private institutions, and 12 are two-year institutions. Two of the four-year institutions are private HBCUs that are publicly supported: Howard University and Tuskegee University. There are 47 publicly supported HBCUs and 34 private HBCUs.

HBCUs serve a specific student population – very low-resourced individuals – to this day. Overall, 85 percent of HBCU students are African American, with 8 percent White, 4 percent Hispanic, 2 percent Asian/Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, and 2 percent two or more races. Over 80 percent of the students attending HBCUs attend publicly supported institutions, and of those, the overwhelming majority of students are low-income (Pell Grant eligible). For first-time, first-year HBCU students, 73 percent are Pell Grant eligible, but that number decreases to 64 percent for all undergraduate students – indicating that students stop-out of school between the time they enter and the second year. By comparison, private HBCUs match the 36 percent national average of first-time, first-year students eligible for Pell Grants as well as for all undergraduates. Each of these schools is a legacy brand with deep meaning and garner respect in the African American community.

HBCUs have an outsized significant impact on their students. For example, HBCUs have educated:

- 80 percent of Black judges

- 50 percent of Black lawyers

- 40 percent of Black Congress members

- 5 percent of CEOs

- over 50 percent of Black teachers

- over 80 percent of all Black doctors and dentists

- 40 percent of Black engineers

- and 30 percent of Black doctoral recipients in STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics) fields.[4]

HBCUs outperform Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs) at preparing Black students for future careers and leadership, especially in STEM. HBCUs continue to lead in awarding African American student undergraduate degrees in STEM with many of those students going on to earn doctorate degrees.[5] Of the top 25 undergraduate institutions whose graduates went on to complete STEM doctorates, 12 HBCUs outproduced prestigious institutions by 64 percent (Harvard, Yale, Brown, Michigan, UC Berkeley, MIT, Cornell, UVA, UNC Chapel Hill, etc.).[6]

For HBCUs, student outcomes include degree attainment (graduation), but also entry into economically sustainable careers that can lift them into the middle class. A recent study reveals that nearly 70 percent of HBCU graduates enter the middle class or higher and that there is less downward mobility for African American students graduating from HBCUs than for those attending PWIs.[7] As stated by the Gallup-USA Funds Minority College Graduates Report, “Despite their well-publicized challenges, in many areas, [HBCUs] are successfully providing Black graduates with a better college experience than they would get at non-HBCUs.”[8]

Findings

Public Information on Credit for Prior Learning at HBCUs

As part of this current study, TMCF first engaged in a review of all publicly available information on HBCU websites to understand how HBCUs utilize PLA. TMCF found that most HBCUs have a policy of accepting some form of PLA, whether Advanced Placement (AP), International Baccalaureate (IB), College Level Examination Program (CLEP), military credit, or placement tests. HBCU website content can be broken down into several buckets related to prior learning: references to recommendations offered by the Council for Adult and Experiential Learning (CAEL); references to alternative credit providers; and military offerings and recommendations offered by the American Council on Education (ACE).

Several HBCUs partner with CAEL to offer “Learning Portfolio Review for Credit,” a method of PLA that involves a detailed evaluation of a portfolio that the student develops to document the learning they received from their work and/or life experience. Prairie View A&M University (PVAMU) in Prairie View, Texas features the Experiential Learning Portfolio (ELP) review, which utilizes the Learning Counts online portfolio assessment offered by CAEL. Through a course, students create a portfolio that is evaluated for demonstrated learning, and Learning Counts makes a recommendation for credit equivalency.[9] Six HBCUs in addition to PVAMU are listed on the CAEL website as member institutions of ELP: Alabama A&M University; Albany State University; Fort Valley State University; Savannah State University (via University System of Georgia); Jarvis Christian College (private); and Medgar Evers College (part of the City University of New York system).

Fayetteville State University’s (FSU) website says that it recognizes certain “Alternative Credit Courses,” which are offered by non-profit organizations and for-profit companies – such as Pearson, Saylor, Ed4Credit, Straighterline, or others.[10] FSU’s Alternative Credit Course program began with its participation in the Alternative Credit Project, a national program of the American Council on Education (ACE), which allowed students to earn up to 64 credits through 104 online and on-demand courses offered by non-profit organizations and for-profit companies. The Alternative Credit Project ended on March 31, 2018, but FSU continues to recognize this pathway to credit accumulation for its students, with prior approval from the university. FSU was the only HBCU that participated in the Alternative Credit Program. An additional six Black colleges provide credit utilizing ACE’s portfolio evaluation, which mirrors PVAMU’s program: Chicago State University, Coppin State University, Jackson State University, Lincoln University in Missouri, Morgan State University, and Virginia State University.

The majority of HBCUs (58 percent), and both national organizations that represent HBCUs, are members of ACE. However, only 12 schools utilize ACE for PLA evaluation through the ACE Credit for Prior Learning Network. This network includes more than 400 accredited colleges and universities “who have articulated policies for accepting prior learning for credit.”[11] Almost all HBCUs accept credit for military training and/or military occupations, and most identify ACE on their websites as one pathway through which veterans can secure credit for their military training. Nevertheless, the number of credits varies by institution. North Carolina Central University’s (NCCU’s) website provides an example: “Veterans, active duty service members, and members of the National Guard and Reserve Components may receive a total of four credits for two courses (basic health and fitness) and three credit hours for speech upon completion of certain military courses approved by the student’s appropriate academic dean.[12] In addition, up to 12 semester hours for military science electives may be awarded based on the number of years on active duty.[13] NCCU will accept up to 30 semester hours of ACE-recommended military credit as transfer work toward a baccalaureate degree.[14] Credit will be awarded as general elective credit or department elective credit. Credit for military service experiences also may be acquired through standardized examinations. Furthermore, NCCU goes on to say, “documented experience that falls outside of the ACE recommendations and/or transfer credit policies of the University will only be considered on a case-by-case basis through a Transfer Credit Appeal.”[15]

Additionally, NCCU has its own Office of Veterans Affairs to support a transition from the military to college for veterans, active service and reserve members, and military dependents. This support includes U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Educational Benefits and additional support to ensure academic success and progression toward graduation. According to the College Factual Website, the VA reports that there are 394 NCCU students who receive the post-9/11 GI Bill funding.[16] This does not include students who are active military.

About 25 percent of Fayetteville State’s students are active military, reservists, veterans, or military dependents.[17] Indeed, the institution has two centers on military bases – at Fort Bragg and at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base. In addition, FSU has a Student Veterans’ Center to support the transition from military life to college, as well as to help secure VA benefits and offer other support. Several other HBCUs have dedicated centers or offices to support veterans, active military, reservists, and military dependents. One FSU junior majoring in criminal justice stated,

“I served in the United States Army for over 15 years and when my military career ended, I decided that I wanted to pursue a career in law enforcement. I felt that it was a great opportunity to get my bachelor’s degree and make a better life for my children. My last station was Fort Bragg and Fayetteville State University had a center on post. I talked with the admissions people and submitted my application and was accepted. They did an audit on my military experience and I received hours towards my degree. My brother attended Virginia State University and he and I will be the only two people in our family to graduate from college. Fayetteville State is a great place, they understand their military students and make sure we are informed.”

While this information demonstrates that HBCUs offer some forms of PLA through official, defined policies, it is not clear how students make use of these offerings, or even how aware current or potential students are about PLA. Moreover, the websites and undergirding policies do not reveal the rationale behind the institutions’ decision to offer what they do. In order to address questions such as these, TMCF conducted case studies at four representative institutions.

Prior Learning at Four Representative HBCUs

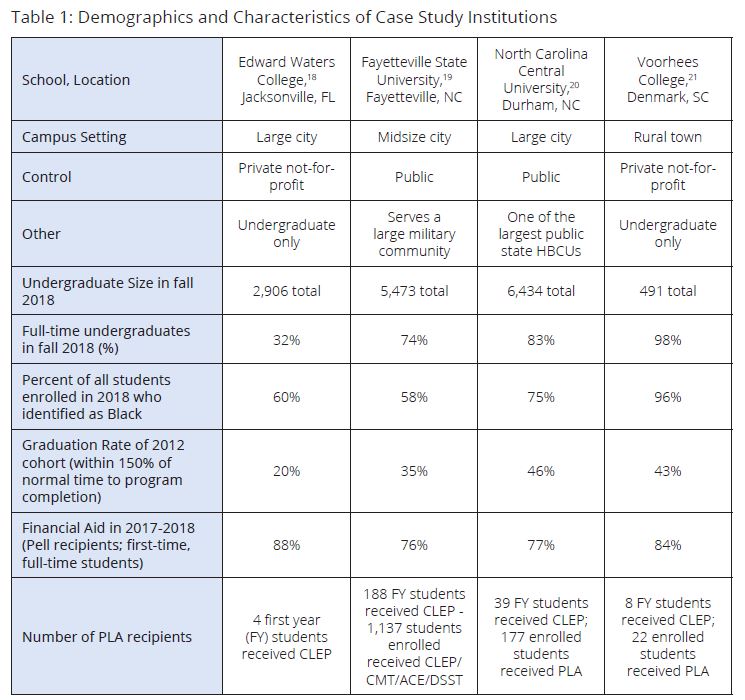

For the case study analysis, TMCF reached out to four HBCUs: Edward Waters College, Fayetteville State University, North Carolina Central University, and Voorhees College. These institutions represent different aspects of HBCUs such as sector, control, size, and location (see Table 1).

TMCF called each school, and the information that TMCF received from the schools was that students primarily utilize CLEP in their final year of school, to ensure that they have fulfilled all of their graduation requirements. Students generally utilize this process after discovering missing classes or requirements during the advising process.

Over the course of this research, TMCF heard from three students attending HBCUs who relied on CLEP (which they refer to as placement exams) in their final year of school to support their graduation efforts.[22] One of the student statements can be found on page one of this brief; the other two are below:

“I have worked since the beginning of my college career at Langston University. Managing classes and work is hard at times but I am a junior now. I took a summer course at another institution but realized later that it couldn’t transfer. Luckily my advisor and major professor told me about taking a placement test. I passed the test and was able to keep my status as a junior. I am set to graduate in 2020 and I owe so much to Langston and the teachers who take the time with students.” – Langston University Junior, Liberal Education Major

“Majoring in music requires a lot of vocal classes in college. I enrolled at Shaw University after attending a performing arts high school up North. When I was set to graduate, I realized I needed an additional course. My advisor and professor gave me the opportunity to take a placement test and graduate on time. My family was so happy. Shaw put forth a real effort to ensure that I graduated on time.” – Shaw University Alumnus, Music

These student testimonials point to a few features of the HBCU environment and student experience that are instructive:

- First is the usage of CLEP to complete requirements and graduate.

- Second is attending multiple institutions – either over the summer or in a progression from a two-year to a four-year college, or multiple four-year colleges.

- Third is commitment to persistence and graduation, which is exemplified by summer coursework.

- Fourth is student unfamiliarity with the mechanisms to attain prior learning credits, which is linked to equity issues.

- Finally, the key catalyst for each student was the advice of a professor and advisor who was more familiar with the mechanisms for achieving credit for prior learning.

At HBCUs, one of the more attractive features for African American students is having professors who are accessible, and whose life journeys mirror the students’. Advising students from a position of cultural, social, and professional experience is critical to student success.

TMCF’s research revealed a dissonance between HBCU policy on PLA acceptance and the actual utilization by students. An analysis of all HBCU websites indicates that most HBCUs offer some forms of PLA through official, defined policies. For example, HBCU websites include references to recommendations offered by CAEL, references to alternative credit providers, military offerings and recommendations offered ACE, and AP and IB programs in high school. Interestingly though, when TMCF conducted interviews at four HBCUs to learn how students utilize PLA, these methods were not mentioned, but rather another: students most often used CLEP in their final year of school in order to get the remaining credits needed to graduate. The interviews suggest that academic advisors are the ones to make this recommendation to students. Another brief in this series, Advising and Prior Learning Assessment for Degree Completion, suggests that “institutional philosophy about PLA may impact the robustness of advising-related policy and support systems for students.”[23] TMCF suggests that a larger qualitative study be conducted across as many HBCUs as possible to better understand what PLA policies and programs are in place and how students learn about and utilize these PLA opportunities.

Prior Learning Assessment, HBCUs, and Equity

While the numbers of students earning credit for PLA tend to be low at most HBCUs, the reasons for this underutilization go far beyond the HBCUs themselves. This can be attributed to two underlying reasons: lack of access to AP/IB in secondary education among the population that the majority of HBCUs serve, and institutional barriers such as lack of funding.

When asked if any students earned credit through AP/IB, the anecdotal response from each of the four representative HBCUs was that the students these schools serve do not have access to these type of courses, and those who do have such access attend either the flagship HBCUs (Spelman, Morehouse, Hampton), flagship state schools (University of Georgia, UNC-Chapel Hill), or elite schools (Harvard, Yale, etc.). Indeed, this response is in alignment with the results of research conducted by TMCF’s Center for Advancing Opportunity, revealing that only 28 percent of fragile (low-income, underserved) community members believe that there is equal access to a college education, even though 87 percent of Black fragile community members believe that a college education is an important pathway to economic success.[24] These findings suggest a lack of access to sufficient college preparatory programs in low-income and underserved communities. The findings from the Center for Advanced Opportunity research study also suggest a mindset that higher education is not attainable for these community members due to lack of services.

Specifically, lack of access to AP and IB courses is endemic for low-income African American communities, and it highlights one of the PLA equity issues for HBCUs and the communities they serve.

While African Americans make up approximately 15 percent of all high school students, they have a lower graduation rate than other groups (78 percent graduation rate for African American students versus 91 percent for Asian/Pacific Islander; 89 percent for White; and 80 percent for Hispanic),[25] make up only 8.8 percent of AP exam takers in 2018, according to the College Board, and only 4.3 percent of students scoring a three or higher on those exams.[26] As for low-income students, the College Board reports that it has doubled the number of these students taking AP exams in the past 10 years, from 16.5 percent in 2008 to 30.8 percent in 2018.[27] Yet it is clear that this increase is not made up of African American low-income students.

A Pipeline of Equity Issues

Although outside the scope of this brief, it is important to recognize the structural racism and inequities across the education continuum that contribute to inequitable access to PLA for Black students. Just some of the factors include:

- Unequal access to early childhood education. For example, only 4 percent of 3- and 4- year-olds in state-funded high-quality early childhood education programs are Black, in a study of 26 states.[28]

- Unequal student discipline for the same behavior (i.e. warnings versus suspensions). For example, Black students are three times as likely to be suspended or expelled compared to white students.[29]

- Unequal treatment in student advising and support of gifted students.[30]

- Access to fewer high-quality, experienced teachers. For example, teachers at public schools with majority Black and Latino populations are more likely to have two years or less of teaching experience compared to teachers at predominately white schools in the same school district.[31]

- Underfunding of K-12 schools that are predominantly Black. For example, school districts that serve predominately students of color receive roughly 2,000 dollars less per student than school districts that serve predominately white populations.[32]

- Educator racial bias leads to these greater disparities in discipline and test scores.[33]

- Lack of training to reduce educator bias.[34]

Students who score a three or higher on an AP exam are more likely to have higher GPAs, high school graduation rates, and are more likely to graduate from college in four years and enter the workforce.[38] Not only does lack of access to AP courses lead to increased expenses for additional years of college – which for HBCU students often translates to greater debt levels – but it also results in lost income. “Failure to promptly complete a degree adds costs—forgone earnings—on top of the extra college expenses [such as tuition and fees]. For example, a fifth year in college costs students forgone earnings of about $32,000, on average. A fifth and sixth year in college implies they’ve forgone an average of $64,000 in earnings.”[39] Overall, using Sallie Mae’s estimate of the average total cost of attending a public college or university for an in-state student of close to $28,000 per year, the total negative financial impact of not having access to AP for a student that graduates college in five or six years is substantial.[40] This is particularly troubling because research has shown interest on school loans and debt have an outsized negative impact on African Americans in particular.[41]

Another issue that fosters inequities between HBCUs and many other types of institutions is institutional funding. Historically, public HBCUs have not received equal per-student state funding as their majority-serving peer institutions. The reasons for this inequity have their roots in endemic racism that can be traced back to the Three-Fifths Compromise that established an inequitable equation between Blacks and Whites for representation in the U.S. House of Representatives, as outlined in the U.S. Constitution. However, this legal codification reflected a deeper societal perception that persists long after the Constitution was amended to eliminate this representational inequity. Lower per-student funding for HBCUs versus PWIs is a remnant of this unequal legal status for persons of African descent in the United States.

The results of this underfunding are manifold. HBCUs – which primarily serve African American and low-income students – rely more on student-generated funding (tuition and state per-student allocations). They have smaller fundraising campaigns and fewer alumni giving as a percentage of their overall revenue. Indeed, HBCUs often do not have endowments and if they do, they are small – negligible in comparison to PWIs. Across each sector, the average per-student endowment assets in 2000 were $1,529 for HBCUs and $5,183 for PWIs.[42] The impact of this lower per-student funding accumulates over the existence of these institutions – with serious results for institutional fiscal health, which in turn can negatively impact accreditation.

Lower per-student funding has led HBCUs to take out loans from both the federal government and the very states that underfunded them in order to bridge their revenue gaps. In addition, to work within their available funds, HBCUs often defer maintenance, training, infrastructure upgrades, and other non-academic initiatives. This has led to inequity in facilities, services, and staff and faculty professional development at HBCUs compared with other institutions.

All these factors combine to make HBCUs less able to effectively recruit students to campus and less able to offer training for recruitment and admissions personnel, both of which lead to fewer opportunities for these schools to reach out to potential students or to engage in a complete set of policies and practices around PLA that is part of the student experience. This includes professional development of faculty and staff, student advising, and providing information and access to PLA methods such as CLEP, challenge exams, external training reviews, portfolio reviews, etc.

It has also led to large debts to the federal and state governments – which HBCUs must service with their limited revenue. In turn, these funding inequities have led to fiscal insecurity for several HBCUs, which can jeopardize their accreditation status. Some states, like North Carolina, have recently acknowledged this historic inequity and changed the per-student funding formula to include additional sums for HBCU students – but this increased formula does not necessarily eliminate more than a century of inequitable funding.

Most recently, Cheyney University in Pennsylvania – the nation’s first HBCU – faced losing its accreditation due to financial instability. Cheyney has a small endowment (about $2 million), and thus is highly dependent on student-generated revenue. Even though today Cheyney receives the largest per-student allocation, this is relatively recent in the history of the country’s oldest HBCU. Recognizing the school’s history and its importance in educating low-income and African American students, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf pledged to forgive $40 million in outstanding state loans to Cheyney which “greatly improved the institution’s financial outlook.”[43]

Cheyney, like many other HBCUs, has endured and seen student success despite historic underfunding. Even after a federal ruling, the state continued to underfund Cheyney: “in 1969, Pennsylvania’s government was found by the federal government to be among 10 state governments operating an openly discriminatory higher education system, and how, in 1999, the [Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education] system signed an agreement with the U.S. Office for Civil Rights that aimed to provide more funding and new programs for Cheyney in an effort to compensate for decades of discrimination. Yet that agreement was never fully executed.”[44] Historic underfunding at Cheyney led to deferred maintenance for its physical plant, resulting in three buildings being slated for demolition and others with visible signs of deterioration. The deteriorated physical environment is not attractive to prospective students and is one reason why open-admissions Cheyney has experienced enrollment decline from 1,470 in 2008 to 695 in Fall 2017 – further hampering its student-based revenue model. This historic lack of funding has also precluded any modernization for Cheyney’s administrative functions. While Cheyney is just one institution, it is an example of how inequitable funding leads to administrative and infrastructure challenges, that feed the declining enrollment spiral, which in turn further reduces its revenue.

Nevertheless, Cheyney University ties at #29 for U.S. News’ Social Mobility ranking.[45] This is the most important function of HBCUs like Cheyney University – social mobility. HBCUs serve a unique student population and have a specific role of facilitating social and economic mobility, moving students from low-income to middle class. HBCUs themselves are engines of equity for low-income and underserved students. Yet evaluation mechanisms like IPEDS, historic funding formulas, and pre-college preparation for the low-income and underserved students that attend HBCUs all represent challenges that these schools must overcome in order to maintain fiscal stability, accreditation, and stable enrollment year after year.

The definition of “first-time, full-time” student status used in IPEDS further exacerbates issues of inequities for HBCUs and many other institutions, whose students do not reflect the “traditional” 18-21-year-old full-time student model. Because IPEDS graduation data count only cohorts of first-time, full-time students, graduation data is unavailable for roughly half of all new undergraduates each fall. Second, IPEDS graduation data captures only completion data for “students who graduated from the same institution where they first enrolled (omitting any who transferred to and later graduated from a different institution)”.[46] According to IPEDS data, Cheyney has a graduation rate of just 15 percent for full-time, first-time, degree/certificate-seeking undergraduates in the 2012 cohort within 150 percent of the normal time to program completion.[47] IPEDS data historically has not tracked students who take more than six years to graduate, or who do not progress or graduate with their first semester cohort.

In the Fall of 2017, IPEDS updated outcome measures they collect as a way to “provide a more nuanced, detailed alternative suite of information about student outcomes … and better coverage of the diverse student populations that have been historically overlooked in traditional graduation rate calculations.”[48] The Outcome Measures variables now include data on “graduation and transfer rates for part-time and non-first-time students, and completion rates for low-income students.”[49] Roughly one third of Cheyney’s entering class each year is comprised of transfer students. Looking at Outcome Measures in IPEDS, these non-first-time students graduate Cheyney at higher rates: 39 percent for full-time students and 33 percent for part-time students than their full-time, first-time peers.[50] While the majority of first-time incoming Cheyney students enroll full-time, of those that enroll part-time, 80 percent have either graduated or reported enrolled at another institution, overall increasing Cheyney’s student outcomes.[51]

Bringing this to PLA – like nearly half of all HBCUs, Cheyney is an open admissions institution, serving low-income and underserved students. Cheyney University’s policy states that it awards credit for AP and IB exams, but the student population it serves does not tend to have a high level of access to these programs. While some Cheyney students have gained college-level learning through life and work experiences, Cheyney currently does not offer students the opportunity to earn credit for this learning via other PLA methods.

TMCF and Delaware State University Pilot Program

Black students attending HBCUs are more likely to graduate at higher rates than their peers from similar non-HBCUs.[52] One recent study compared HBCUs to institutions with similar characteristics such as size, sector, financial resources, and populations of students with similar levels of income and academic preparation, and found that “African American students attending HBCUs are up to 33 percent more likely to graduate than African American students attending a similar non-HBCU.” Even still, as the previous section lays out, HBCUs are historically underfunded and underresourced. In addition, most of the students attending these institutions are from low-income families.

One outcome of the lack of resources for both students attending HBCUs and the institutions themselves is that a large number of HBCU students end their college careers prior to earning their degrees, or do not complete their degrees with their entering cohort. The latter phenomenon, in which students fall out of their IPEDS cohort leads to inaccurate completion data for HBCUs, which makes them appear to be less successful – and therefore less attractive – to prospective students. The former phenomenon, which is particularly true of low-income students that HBCUs serve, leads to a large number of former HBCU students who have not earned their college degrees, but have ended their education due to lack of financial resources.

TMCF’s business model attempts to fill in resource gaps for its member-schools, providing student supports that the schools can’t provide, for students whose own resources also are limited. As the latest example, TMCF and its member-school Delaware State University (DSU) have outlined a pilot program to attract students who stopped out of DSU prior to completing their degree. This program can serve as a potential model for HBCUs to recruit these former students and provide PLA for their college-level learning gained through life or work experience, while enrolling them in a degree completion program. During the planning phase of this pilot program, TMCF engaged Tyton Partners to conduct research on DSU non-completers through data analysis, surveys, and focus groups. The results of this research are instructive, as these students have accumulated significant credits that would count toward degree completion.

An analysis of 2014 data from the National Student Clearinghouse indicates that there are about 2 million African American non-completers (“some college, no degree”) with 60 or more credits, and of those approximately 366,000 attending HBCUs.[53] TMCF and DSU are targeting students with 90 or more credits completed (2 semesters or less to complete their degrees), which numbers 175,000 former HBCU students. Since 2014, there has been a 22 percent increase in the number of non-completers – both in overall numbers and those who attended an HBCU. The 2019 statistics reveal that there are approximately 466,000 HBCU-educated non-completers with 60 or more credits, and 212,000 with 90 or more.

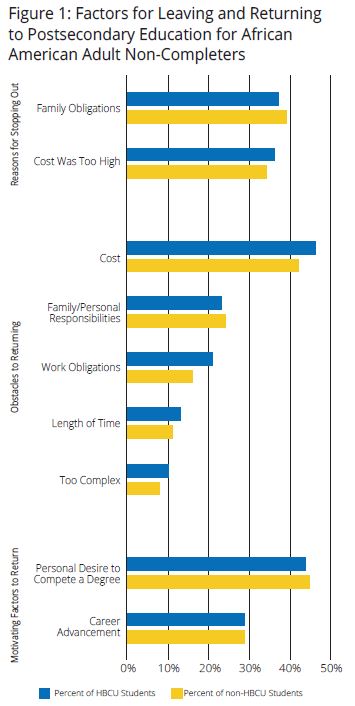

Through focus groups and surveys of about 1,000 African American adult non-completers, of which 250 attended HBCUs, 66 percent of the former HBCU students have some college but no degree, while 34 percent have an associate’s degree – a similar proportion to the non-HBCU non-completers surveyed. For the purpose of this PLA analysis, the most relevant information was about reasons for stopping out, obstacles to returning, and reasons that those surveyed might return (see Figure 1).

Family obligations and cost were both cited as reasons for stopping out of postsecondary education and as obstacles to return. Yet, 65 percent of all survey respondents who attended HBCUs are motivated to return and complete their degree. The overwhelming majority of these students reported having a positive experience at their HBCU.

TMCF’s pilot program with DSU is designed to recruit non-completers, register them, and support their completion. This new model is poised to create an on-ramp for adult learners to complete their degrees and advance their economic potential. Part of the program will award PLA for college-level learning acquired through work and/or life experiences, where applicable, which is an enticement for adult learners. Because Delaware State does not have an existing PLA program, it has chosen to partner with Southern New Hampshire University – which has strong PLA options – to provide that service. The pilot program is starting fall semester 2020; initial findings from this pilot program will be shared when available.

Recommendations

As this brief has outlined, low-income and underserved community residents – the population that HBCUs serve – desire a college education and understand its importance in improving economic status. Yet, the education available in their communities does not prepare them adequately to take advantage of prior learning assessments like AP and IB. Although there are several distinct and endemic factors contributing to low PLA participation by HBCU students, TMCF can make the following recommendations:

- Improve access to AP and IB programming in high schools for low-income and minority students, so they can be better prepared for college. One way to do this is for philanthropic funders and/or the federal government to support African American teachers, over half of which are educated at HBCUs. This would include professional training and support that facilitates their longevity in the classroom, as well as training as AP teachers. TMCF created its Teacher Quality & Retention Program (TQRP) to identify, train, and support preservice and early career teachers educated at an HBCU. This limited five-year fellowship has resulted in an 85 percent retention rate for participants, and is the only such program exclusively focused on HBCU-educated teachers.

- Train middle school and high school counselors to advise students about dual credit opportunities, AP courses and tests, and pathways to college. One option for this recommendation is to provide funding for a series of webinars or a virtual convening (to reach as many counselors as possible) that would build capacity for high school and middle school counselors in this area. This training could be offered through a national association for school counselors, funded by philanthropists focused on improving education, or governmental bodies.

- Support HBCU efforts to reach out to current and former military students – specifically with information about receiving credit for military experience, to attract these students to HBCUs for degree completion. Steps to achieve this recommendation include providing support for HBCUs to educate potential students about military credits and support their engagement in applying for and receiving these credits. This also would entail training dedicated HBCU staff in recruitment, admissions, and enrollment areas.

- Support efforts to create policies and practices around PLA at HBCUs, so that students know about and can earn credit for their college-level learning acquired in work and life experiences, such as portfolio creation and review, as well as community outreach, so that HBCUs can attract students seeking degree completion or career advancement. Targeted HBCU staff would need to be trained on how this option would work and institutions would need the funding to reach out to potential students, as well as to support the portfolio creation and review.

- Provide professional development opportunities for HBCU advising staff and faculty. Ensuring that students are advised from a position of cultural, social, and professional experience is critical to student success.

- Forgive state and federal loans to HBCUs, as an initial step toward rectifying historic funding deficits and stabilizing HBCUs, so they can attract and support more students and put more resources to training staff on opportunities related to prior learning, student retention, and student success support.

Conclusion

TMCF’s research revealed a dissonance between HBCU policy on PLA acceptance and the actual utilization by students. As TMCF dug a bit deeper into utilization, we understood that most HBCU students did not have equal access to pre-college PLA programs (AP/IB) in their high schools. We also discovered that individual academic advisors often recommended that students utilize CLEP in order to complete outstanding graduation requirements. This reflects the general culture within HBCUs wherein personnel need to accomplish more with fewer resources, due to historic underfunding and under-resourcing. In the near-term, the pilot program between TMCF, Delaware State University, and Southern New Hampshire University, might offer a model for institutions looking to improve tuition revenue stream and increase HBCU student completion, while simultaneously helping students earn credits for college-level learning they have acquired outside of the institution through work and life experiences.

Endnotes

[1] Carol Billingham and Joseph Travaglini, “Predicting Adult Academic Success in an Undergraduate Program,” Alternative Higher Education 5, no. 3 (1981), 169-182; Walter Stephen Pearson, Enhancing Adult Student Persistence: The Relationship between Prior Learning Assessment and Persistence Toward the Baccalaureate Degree (Ames, IA: Iowa State University, 2000); Grant Snyder, Persistence of Community College Students Receiving Credit for Prior Learning (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1990).

[2] Shirley Freers, An Evaluation of Adult Learners’ Perceptions of a Community College’s Assessment of Prior Learning Program, (Malibu, CA: Pepperdine University, 1994).

[3] Rebecca Klein-Collins, Fueling the Race to Postsecondary Success: A 48-Institution Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes (Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2010), accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://www.cael.org/pla/publication/fueling-the-race-to-postsecondary-success; Brent Sargent, An Examination of the Relationship Between Completion of a Prior Learning Assessment Program and Subsequent Degree Program Participation, Persistence, and Attainment (Sarasota, FL: University of Sarasota, 1999).

[4] Thurgood Marshall College Fund, “Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs),” accessed on 28 August 2020 at http://tmcf.org/about-us/our-schools/hbcus; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, “Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Higher Education Desegregation,” March 1991, accessed on 28 August 2020 from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq9511.html; National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2015 (Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation; 2015) accessed on 28 August 2020 at https://www.ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/.

[5] U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, “Historically Black Colleges and Universities.”

[6] Jarrett L. Carter, “For HBCUs, the Proof Is in the Productivity,” The Huffington Post, 27 January 2014, accessed on 28 August 2020 at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jarrett-l-carter/hbcus-the-proof-is-in-productivity_b_4665765.html.

[7] Robert A. Nathenson, Andrés Castro Samayoa, and Marybeth Gasman, Moving Upward and Onward: Income Mobilitity at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers Graduate School of Education, Center for MSIs, 2019), accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://cmsi.gse.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/EMreport_R4_0.pdf.

[8] Gallup-USA Funds Minority College Graduates Report. Washington, DC: Gallup. 2015, p. 5.

[9] Prairie View A&M University, “Prior Learning Assessment,” accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.pvamu.edu/student-success/sass/testing/pla/.

[10] For more information on some of these alternative credit providers, see the following brief that is part of this series: Julie Uranis and Van Davis, Recent Developments in Prior Learning (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education), forthcoming.

[11] American Council on Education, “ACE Credit-Accepting Institutions,” accessed on 25 August 2020 at https://www.acenet.edu/Programs-Services/Pages/Credit-Transcripts/Credit-Accepting-Institutions.aspx#:~:text=%E2%80%8BCredit%20for%20Prior%20Learning,credit%2C%20including%20ACE%20credit%20recommendations.

[12] North Carolina Central University, “Undergraduate Admissions,” accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://ecatalog.nccu.edu/content.php?catoid=13&navoid=1388#:~:text=Veterans%2C%20active%20duty%20service%20members,the%20student’s%20appropriate%20academic%20dean.

[13] North Carolina Central University, “REG -10.01.5 – Transfer of Undergraduate Credit Regulation,” accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://legacy.nccu.edu/policies/retrieve.cfm?id=482.

[14] North Carolina Central University, “Office of Transfer Services,” accessed on 1 July 2020 at http://ecatalog.nccu.edu/content.php?catoid=12&navoid=1326.

[15] North Carolina Central University, “Office of Transfer Services.”

[16] College Factual, “Veteran North Carolina Central University Students Services & Resources,” accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.collegefactual.com/colleges/north-carolina-central-university/student-life/veterans/.

[17] The University of North Carolina System, “Fayetteville State University,” accessed on 15 July 2020 at https://www.northcarolina.edu/institution/fayetteville-state-university/.

[18] Research conducted by Dr. Paul K. Baker, Director of the Quality Enhancement Program (QEP), North Carolina Central University, using National Center for Education Statistics, “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Edward Waters College,” accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=133526.

[19] Research conducted by Dr. Paul K. Baker, Director of the Quality Enhancement Program (QEP), North Carolina Central University, using National Center for Education Statistics, “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Fayetteville State University,” accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=198543.

[20] Research conducted by Dr. Paul K. Baker, Director of the Quality Enhancement Program (QEP), North Carolina Central University, using National Center for Education Statistics, “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, North Carolina Central University,” accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=199157.

[21] Research conducted by Dr. Paul K. Baker, Director of the Quality Enhancement Program (QEP), North Carolina Central University, using National Center for Education Statistics, “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Voorhees College” accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=218919.

[22] Research conducted by Dr. Paul K. Baker, Director of the Quality Enhancement Program (QEP), North Carolina Central University.

[23] For more information on student advising practices related to PLA, see the following brief that is part of this series: Alexa Wesley and Amelia Parnell, Advising and Prior Learning Assessment for Degree Completion, (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, August 2020), 6, accessed on 3 September 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/.

[24] Gallup, Inc., The State of Opportunity in America: Understanding Barriers and Identifying Solutions, (Washington, D.C.: Gallup, Inc., 2020), accessed on 9 September 2020 at

[25] National Center for Education Statistics, “Public High School Graduation Rates,” accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_coi.asp.

[26] College Board, “AP Program Results Class of 2018,” accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://reports.collegeboard.org/archive/2018/ap-program-results/class-2018-data.

[27] College Board, “AP Program Results.”

[28] Carrie Gillispie, Young Learners, Missed Opportunities: Ensuring that Black and Latino Children Have Access to High-Quality State-Funded Preschool (Washington, D.C.: The Education Trust, 2019), accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edtrustmain.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/05162154/Young-Learners-Missed-Opportunities.pdf.

[29] U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, Civil Rights Data Collection Data Snapshot: School Discipline, (Washington D.C., March 2014), accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-discipline-snapshot.pdf; American Civil Liberties Union, School-to-Prison Pipeline, (New York: NY, no date), accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/school-prison-pipeline/school-prison-pipeline-infographic.

[30] Kayla Patrick, Allison Socol, and Ivy Morgan, Inequities in Advanced Coursework: What’s Driving Them and What Leaders Can Do (Washington, D.C.: The Education Trust, 2020), accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edtrust.org/press-release/black-and-latino-students-shut-out-of-advanced-coursework-opportunities/; College Board, The 10th Annual AP Report to the Nation (New York, NY: The College Board, 2014), 29, accessed on 10 July 2020 at https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/ap/rtn/10th-annual/10th-annual-ap-report-to-the-nation-single-page.pdf.

[31] David S Knight, “Are School Districts Allocating Resources Equitably? The Every Student Succeeds Act, Teacher Experience Gaps, and Equitable Resource Allocation,” Educational Policy 33, no. 4 (2019), 615-649.

[32] EdBuild, “Nonwhite School Districts Get 23 Billion Less,” accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edbuild.org/content/23-billion.

[33] Mark J. Chin, David M. Quinn, Tasminda K. Dhaliwal, and Virginia S. Lovison, “Bias in the Air: A Nationwide Exploration of Teachers’ Implicit Racial Attitudes, Aggregate Bias, and Student Outcomes,” in Educational Researcher (2020).

[34] Chin, Quinn, Dhaliwal, and Lovison, “Bias is in the Air”; Diana Lambert, “California Schools Chief Launches Campaign Against Racial Bias,” EdSource (5 June 2020), accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edsource.org/2020/california-schools-chief-launches-campaign-against-racial-bias/633134.

[35] College Board, The 10th Annual AP Report.

[36] Xianglei Chen, STEM Attrition: College Students’ Paths Into and Out of STEM Fields (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2013), 28, accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014001rev.pdf.

[37] Rebecca Klein-Collins, Jason Taylor, Carianne Bishop, Peace Bransberger, Patrick Lane, and Sarah Leibrandt, The PLA Boost Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes, (Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning), forthcoming.

[38] College Board, AP Student Success at the College Level (New York, NY: The College Board, 2016), accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://aphighered.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/ap-student-success-college-recent-research.pdf.

[39] Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch, Education Pays 2016: Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society (New York, NY, 2016) as cited in ‘AP Program Results Class of 2018’ accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://reports.collegeboard.org/archive/2018/ap-program-results/class-2018-data.

[40] Jennifer Ma, et al., Education Pays.

[41] Judith Scott-Clayton and Jing Li, Black-White Disparity in Student Loan Debt More than Triples after Graduation (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institute), accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://www.brookings.edu/research/black-white-disparity-in-student-loan-debt-more-than-triples-after-graduation/.

[42] Nathenson, Samayoa, and Gasman, Moving Upward and Onward.

[43] Susan Snyder, “A Boost for Cheyney University: The School Will Keep Its Accreditation,” The Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 November 2019, accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.inquirer.com/education/cheyney-university-accreditation-middle-states-finances-20191125.html.

[44] Kellie Woodhouse, “An HBCU Fights to Survive,” Inside Higher Ed, 15 September 2015, accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/09/15/problems-mount-cheyney-university-oldest-hbcu.

[45] U.S. News & World Report, “Cheyney University of Pennsylvania,” accessed on 10 July 2020 at https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/cheyney-university-3317/overall-rankings.

[46] Institute for Higher Education Policy, Postsec Data, An Evolution of Measuring Student Outcomes in IPEDS (Washington, D.C.: Institute for Higher Education Policy, December 2014), accessed on 27 July 2020 at http://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/postsecdata/docs/data-at-work/postsecdata_gr-om_explainer.pdf.

[47] National Center for Education Statistics, “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania” accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=211608.

[48] Peace Bransberger and Colleen Falkenstern, WICHE Insights: Exploring IPEDS Outcome Measures in the WICHE Region (Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, April 2018), accessed on 25 August 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/WICHE-Insights-04518.pdf.

[49] Institute for Higher Education Policy, Postsec Data, An Evolution.

[50] National Center for Education Statistics, “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania.”

[51] National Center for Education Statistics, “Degree/Certificate-seeking Undergraduate Entering Students in the Adjusted Cohort and Status 8 Years After Entry, by Outcome Category, Entering and Attendance Status,” accessed on 27 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/SummaryTable.aspx?templateId=9023&tableYear=2018.

[52] David A. R. Richards and Janet T. Awokoya, Understanding HBCU Retention and Completion (Fairfax, VA: Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute, UNCF, 2012), accessed on 28 August 2020 at https://cdn.uncf.org/wp-content/uploads/PDFs/Understanding_HBCU_Retention_and_Completion.pdf; Ethan K. Gordon, Zackary B. Hawley, Ryan Carrasco Kobler, and Jonathan C. Rork, “The Paradox of HBCU Graduation Rates,” Research in Higher Education (28 May 2020), accessed on 28 August 2020 at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-020-09598-5.

[53] From an internal TMCF report.

References

American Civil Liberties Union. School-to-Prison Pipeline. New York: NY, (no date). Accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://www.aclu.org/issues/juvenile-justice/school-prison-pipeline/school-prison-pipeline-infographic.

American Council on Education. “ACE Credit-Accepting Institutions.” Accessed on 25 August 2020 at https://www.acenet.edu/Programs-Services/Pages/Credit-Transcripts/Credit-Accepting-Institutions.aspx#:~:text=%E2%80%8BCredit%20for%20Prior%20Learning,credit%2C%20including%20ACE%20credit%20recommendations.

Billingham, Carol and Joseph Travaglini. “Predicting Adult Academic Success in an Undergraduate Program.” Alternative Higher Education 5, no. 3 (1981), 169-182

Bransberger, Peace and Colleen Falkenstern. WICHE Insights: Exploring IPEDS Outcome Measures in the WICHE Region. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, April 2018. Accessed on 25 August 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/WICHE-Insights-04518.pdf.

Carter, Jarrett L. “For HBCUs, the Proof Is in the Productivity.” The Huffington Post, 27 January 2014. Accessed on 28 August 2020 at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jarrett-l-carter/hbcus-the-proof-is-in-productivity_b_4665765.html.

Chen, Xianglei. STEM Attrition: College Students’ Paths Into and Out of STEM Fields. Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, 2013, 28. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2014/2014001rev.pdf.

Chin, Mark J., David M. Quinn, Tasminda K. Dhaliwal, and Virginia S. Lovison. “Bias in the Air: A Nationwide Exploration of Teachers’ Implicit Racial Attitudes, Aggregate Bias, and Student Outcomes.” Educational Researcher (2020).

College Board. “AP Program Results Class of 2018.” Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://reports.collegeboard.org/archive/2018/ap-program-results/class-2018-data.

College Board. The 10th Annual AP Report to the Nation. New York, NY: The College Board, 2014. Accessed on 10 July 2020 at https://secure-media.collegeboard.org/digitalServices/pdf/ap/rtn/10th-annual/10th-annual-ap-report-to-the-nation-single-page.pdf.

College Board. AP Student Success at the College Level. New York, NY: The College Board, 2016. Accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://aphighered.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/ap-student-success-college-recent-research.pdf.

College Factual. “Veteran North Carolina Central University Students Services & Resources.” Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.collegefactual.com/colleges/north-carolina-central-university/student-life/veterans/.

EdBuild. “Nonwhite School Districts Get 23 Billion Less.” Accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edbuild.org/content/23-billion.

Freers, Shirley. An Evaluation of Adult Learners’ Perceptions of a Community College’s Assessment of Prior Learning Program. Malibu, CA: Pepperdine University, 1994.

Gallup, Inc. The State of Opportunity in America: Understanding Barriers and Identifying Solutions. Washington, D.C.: Gallup, Inc, 2018. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://www.advancingopportunity.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/The-State-of-Opportunity-in-America-Report-Center-for-Advancing-Opportunity.pdf.

Gillispie, Carrie. Young Learners, Missed Opportunities: Ensuring that Black and Latino Children Have Access to High-Quality State-Funded Preschool. Washington, D.C.: The Education Trust, 2019. Accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edtrustmain.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/05162154/Young-Learners-Missed-Opportunities.pdf.

Gordon, Ethan K., Zackary B. Hawley, Ryan Carrasco Kobler, and Jonathan C. Rork. “The Paradox of HBCU Graduation Rates.” Research in Higher Education (28 May 2020). Accessed on 28 August 2020 at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11162-020-09598-5.

Institute for Higher Education Policy, Postsec Data. An Evolution of Measuring Student Outcomes in IPEDS. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Higher Education Policy, December 2014. Accessed on 27 July 2020 at http://www.ihep.org/sites/default/files/uploads/postsecdata/docs/data-at-work/postsecdata_gr-om_explainer.pdf.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca. Fueling the Race to Postsecondary Success: A 48-Institution Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes. Chicago, IL: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, 2010. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://www.cael.org/pla/publication/fueling-the-race-to-postsecondary-success.

Klein-Collins, Rebecca, Jason Taylor, Carianne Bishop, Peace Bransberger, Patrick Lane, and Sarah Leibrandt. The PLA Boost Results from a 72-Institution Targeted Study of Prior Learning Assessment and Adult Student Outcomes. Indianapolis, IN: Council for Adult and Experiential Learning, forthcoming.

Knight, David S. “Are School Districts Allocating Resources Equitably? The Every Student Succeeds Act, Teacher Experience Gaps, and Equitable Resource Allocation.” Educational Policy 33, no. 4 (2019), 615-649.

Lambert, Diana. “California Schools Chief Launches Campaign Against Racial Bias.” EdSource (5 June 2020), accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edsource.org/2020/california-schools-chief-launches-campaign-against-racial-bias/633134.

Ma, Jennifer, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch. Education Pays 2016: Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society. New York, NY, 2016. As cited in ‘AP Program Results Class of 2018’ accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://reports.collegeboard.org/archive/2018/ap-program-results/class-2018-data.

Nathenson, Robert, Andrés Castro Samayoa, and Marybeth Gasman. Moving Upward and Onward: Income Mobility at Historically Black Colleges and Universities. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University School of Education. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://cmsi.gse.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/EMreport_R4_0.pdf.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Degree/Certificate-seeking Undergraduate Entering Students in the Adjusted Cohort and Status 8 Years After Entry, by Outcome Category, Entering and Attendance Status.” Accessed on 27 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/SummaryTable.aspx?templateId=9023&tableYear=2018.

National Center for Education Statistics. “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Edward Waters College.” Accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=133526.

National Center for Education Statistics. “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Fayetteville State University.” Accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=198543

National Center for Education Statistics. “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, North Carolina Central University.” Accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=199157.

National Center for Education Statistics. “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Voorhees College.” Accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=218919.

National Center for Education Statistics. “IPEDS Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, Look Up an Institution, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania.” Accessed on 13 July 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/datacenter/institutionprofile.aspx?unitId=211608.

National Center for Education Statistics. “Public High School Graduation Rates.” Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_coi.asp.

National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2015. Arlington, VA: National Science Foundation, 2015. Accessed on 28 August 2020 at https://www.ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/.

North Carolina Central University. “Office of Transfer Services.” Accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://ecatalog.nccu.edu/content.php?catoid=12&navoid=1326.

North Carolina Central University. “Undergraduate Admissions.” Accessed on 1 June 2020 at http://ecatalog.nccu.edu/content.php?catoid=13&navoid=1388#:~:text=Veterans%2C%20active%20duty%20service%20members,the%20student’s%20appropriate%20academic%20dean.

North Carolina Central University. “REG -10.01.5 – Transfer of Undergraduate Credit Regulation.” Accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://legacy.nccu.edu/policies/retrieve.cfm?id=482.

Patrick, Kayla, Allison Socol, and Ivy Morgan. Inequities in Advanced Coursework: What’s Driving Them and What Leaders Can Do. Washington, D.C.: The Education Trust, 2020. Accessed on 14 September 2020 at https://edtrust.org/press-release/black-and-latino-students-shut-out-of-advanced-coursework-opportunities/.

Pearson, Walter Stephen. Enhancing Adult Student Persistence: The Relationship between Prior Learning Assessment and Persistence Toward the Baccalaureate Degree. Ames, IA: Iowa State University, 2000.

Prairie View A&M University. “Prior Learning Assessment.” Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.pvamu.edu/student-success/sass/testing/pla/.

Richards, David A. R. and Janet T. Awokoya. Understanding HBCU Retention and Completion. Fairfax, VA: Frederick D. Patterson Research Institute, UNCF, 2012. Accessed on 28 August 2020 at https://cdn.uncf.org/wp-content/uploads/PDFs/Understanding_HBCU_Retention_and_Completion.pdf;

Sargent, Brent. An Examination of the Relationship Between Completion of a Prior Learning Assessment Program and Subsequent Degree Program Participation, Persistence, and Attainment. Sarasota, FL: University of Sarasota, 1999.

Scott-Clayton, Judith and Jing Li. Black-White Disparity in Student Loan Debt More than Triples after Graduation. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institute. Accessed on 1 July 2020 at https://www.brookings.edu/research/black-white-disparity-in-student-loan-debt-more-than-triples-after-graduation/.

Snyder, Grant. Persistence of Community College Students Receiving Credit for Prior Learning. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania, 1990.

Snyder, Susan. “A Boost for Cheyney University: The School Will Keep Its Accreditation.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 November 2019. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.inquirer.com/education/cheyney-university-accreditation-middle-states-finances-20191125.html.

The University of North Carolina System. “Fayetteville State University.” Accessed on 15 July 2020 at https://www.northcarolina.edu/institution/fayetteville-state-university/.

Thurgood Marshall College Fund. “Historically Black Colleges & Universities (HBCUs).” Accessed on 28 August 2020 at http://tmcf.org/about-us/our-schools/hbcus.

Uranis, Julie and Van Davis. Recent Developments in Prior Learning. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, forthcoming.

U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights. “Historically Black Colleges and Universities and Higher Education Desegregation.” March 1991. Accessed on 28 August 2020 from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/hq9511.html.

U.S. News & World Report. “Cheyney University of Pennsylvania.” Accessed on 10 July 2020 at https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/cheyney-university-3317/overall-rankings.

Wesley, Alexa and Amelia Parnell. Advising and Prior Learning Assessment for Degree Completion. Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, August 2020. Accessed on 3 September 2020 at https://www.wiche.edu/key-initiatives/recognition-of-learning/.

Woodhouse, Kellie. “An HBCU Fights to Survive.” Inside Higher Ed, 15 September 2015. Accessed on 1 June 2020 at https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2015/09/15/problems-mount-cheyney-university-oldest-hbcu.

About the Author

- Amy D. Goldstein is assistant vice president of organizational development for the Thurgood Marshall College Fund, bringing over 30 years of experience in the non-profit community on the national, international and local levels. At TMCF, Amy supports HBCU capacity building initiatives as part of her duties. Born in Detroit, Amy grew up with a deep appreciation of the importance of history and culture to diverse communities, as well as with a strong legacy of activism. Amy put her training to work in a variety of agencies. In each position, she reached out to traditional and non-traditional partners, achieved seemingly “unachievable” goals and supported this work with strategic fundraising. Moving to Houston at the end of 2005, Amy worked for a variety of local groups, helping them to meet their goals in outreach and development. Amy holds a B.A. in Middle East history and politics from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, and an M.A. in cultural history from the Jewish Theological Seminary.

About the organization

- Established in 1987, the Thurgood Marshall College Fund (TMCF) is the nation’s largest organization exclusively representing the Black College Community. TMCF member-schools include the publicly supported Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) and Predominantly Black Institutions (PBI), enrolling nearly 80% of all students attending Black colleges and universities. Through scholarships, capacity building and research initiatives, innovative programs, and strategic partnerships, TMCF is a vital resource in the higher education space. The organization is also the source for top employers seeking top talent for competitive internships and good jobs.

Copyright

Copyright © 2020 by the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education

3035 Center Green Drive, Boulder, CO 80301-2204

An Affirmative Action/Equal Opportunity Employer

Printed in the United States of America

Publication number 4a500130

Disclaimer

This publication was prepared by Amy D. Goldstein of Thurgood Marshall College Fund. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Lumina Foundation, its officers, or its employees, nor do they represent those of Strada Education Network, its officers, or its employees.